Nitrogen, war, food

In 1918 the Nobel Prize for Chemistry was given to Fritz Haber: he invented a method for synthesizing ammonia - that is, nitrogen 'fixed' with hydrogen - a chemical vital for organic life. The process was used during the First World War to make munitions: the allies got theirs from South American mines. Without industrial-scale production of ammonia, the war would have been considerably shorter. Verdun, for example - where a service took place today on WWI's 90th annivesary - was bombarded with a hundred thousand shells an hour - an hour! - at the start of the battle. (As well as a hundred thousand gas shells a day: Haber was instrumental in the development of gas warfare. Randomly, I now realise he was the subject of a brilliant Radio 4 play I caught the second half of. His scientist wife committed suicide. If the play is to be believed, this was to shock him into realising the monster he'd become. I buy that: radio 4 fiction will do for me as a factual source.)

The Haber-Bosch process, according to Wikipedia, now sustains a third of the world's population. It was / is a vital element of the Green Revolution - Nitrogen boosts crop levels linearly, up to a point. The other element of that revolution was developing strains capable of physically holding all that nitrogen without breaking.

There are those who'd argue Haber's work was just as destructive in agriculture as in war: I'm not one of them. Here's a quote from a review of Duncan Brown's 'Feed or Feedback' [1], a lovely summary of the argument:

Western farming in its current industrial phase provides greater densities of population at the cost of ecosystem collapse. Economic efficiency is turning fields into mechanised monocultures – only maintainable with heavy supplies of fertilisers, water and energy. The subsequent export of 'agribusiness' to the agrarian countries – accelerated in the 1960s with the 'Green Revolution' – has brought the planet into a worrisome critical state. If we were serious about 'sustainability' and genuinely concerned with the prospective collapse of the world’s population, our systems of production ought to be redesigned so that intensive recycling of nutrients is rendered possible again. In Brown’s opinion, such a remodelling is tantamount to the conversion of giant agribusinesses into smaller organic farms, and the relocation of population around the centres of agricultural production. [2]

That captures most of the things your common-or-garden 'alternative food network' (AFN) academic might think. The reason I can't include myself in that camp is because its often so unreflective: 'AFNs are anti-corporate, therefore I support them.' An extreme example:

Organic agriculture and localised food systems regenerate local economies, revitalizes local knowledge, and creates enormous social wealth, and could counteract juvenile delinquency, gang violence and suicides in socially deprived areas. [3]

Gosh. Well, maybe it could. But the stark facts are difficult to surmount: the Green Revolution turned Mexico from a wheat-importing to an exporting country in 20 years.

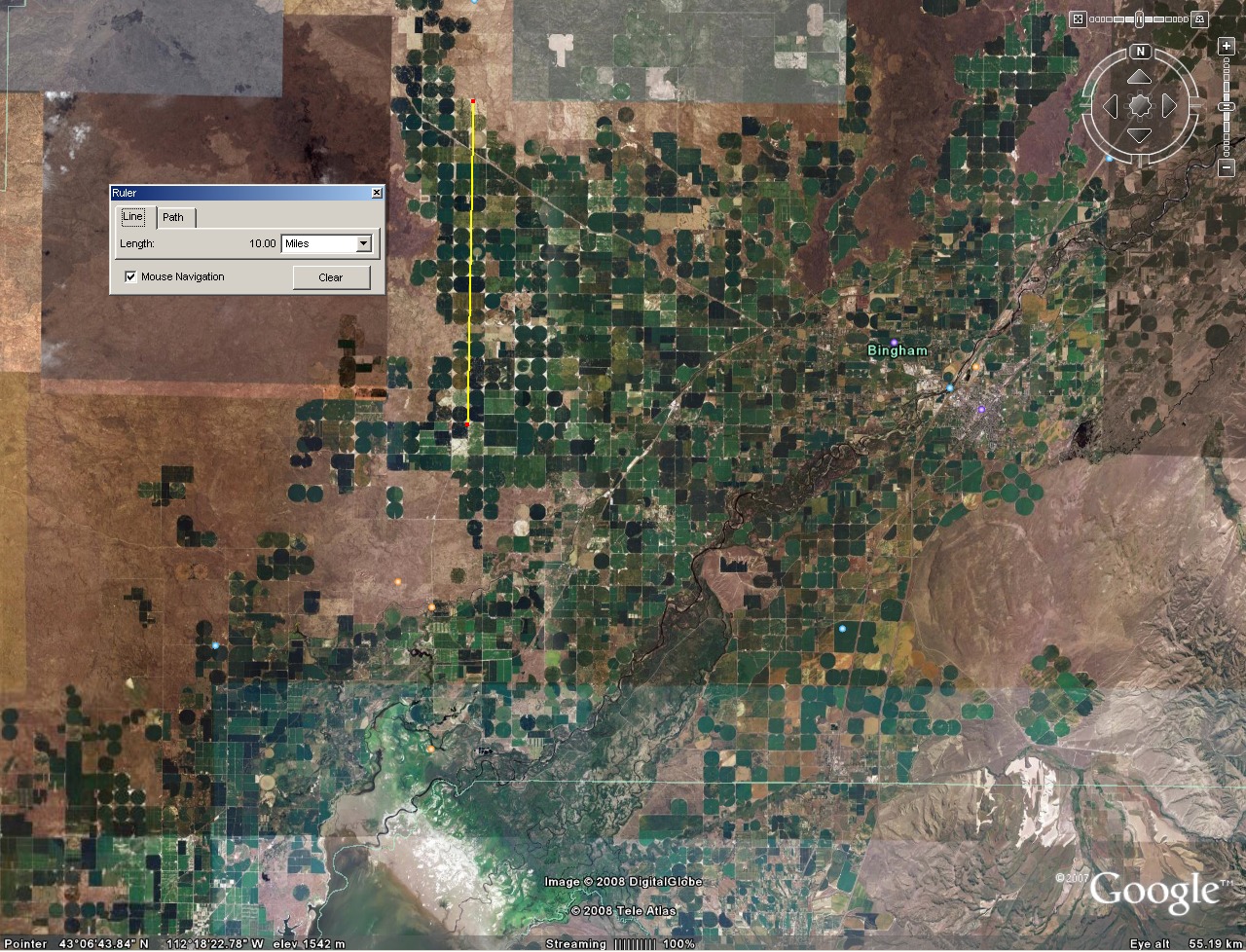

There are plenty of reasons why Green Revolution-style food production might go wrong: it's based on changing the soil to match the crop, it requires huge petro-energy input - and of course industrial amounts of synthetic ammonia got through the Haber process. It lends itself to large-scale, ecologically destructive production, needing vast irrigation - typified by amazing shots of pivot irrigation. (Each of those fields is about half a mile in diameter.)

But do we have an alternative? This is where I part company from many AFNers. Without the numbers, it's hard to argue that alternative food networks are anything but a lifestyle choice (as Tim Harford has pointed out.) That doesn't mean you shouldn't buy what you want, or work on groovy local food projects, but it does mean being cautious about attacking the mainstream.

'Productivist' is a term of abuse in much AFN writing - in the same boat as 'consumerist'. But this subject obviously, manifestly should be about production levels. As the architect of the Green Revolution, Norman Borlaug has supposedly argued:

Some of the environmental lobbyists of the Western nations are the salt of the earth, but many of them are elitists. They’ve never experienced the physical sensation of hunger. They do their lobbying from comfortable office suites in Washington or Brussels. If they lived just one month amid the misery of the developing world, as I have for fifty years, they’d be crying out for tractors and fertilizer and irrigation canals and be outraged that fashionable elitists back home were trying to deny them these things.

Well, here I am again: getting in touch with my inner Tory. In the weekly roulette wheel of my PhD, it's the above I'm supposed to be modelling, more or less. What level of food production can a system maintain if energy inputs start dropping off? How much can that energy loss be met through other means? (Well - there'll be a lot more jobless people laying about, and the inverse size-yield relationship tells us that might actually be more productive than our current system...) What sort of geographic equilibria might come about? What role might knowledge networks play - as they do in industrial innovation?

Current nitrogen flows probably closely mimick other international flows. If only we could stick some RFID tags on a few molecules...

One little Nitrogen-related story to finish on: the FT reports on a company that plans to use ammonia as a conveniently mobile hydrogen storage source for vehicles. So -

a) get hydrogen either from natural gas or through electrolysis - taking huge amounts of power

b) convert into ammonia through very high pressure, high energy methods

c) Convert it back to hydrogen in the car.

Genius.

1. A. Duncan Brown, Feed or Feedback: Agriculture, Population Dynamics and the State of the Planet (International Books,Netherlands, 2004).

2. Thomas-Pellicer, R., Book Reviews, Environmental Politics,14:4,551 — 575

3. Ho, M., 2008. Food Without Fossil Fuels Now. Available at: http://www.i-sis.org.uk/foodWithoutFossilFuels.php [Accessed April 8, 2008].

Recent comments

21 weeks 6 days ago

2 years 12 weeks ago

2 years 12 weeks ago

2 years 14 weeks ago

2 years 15 weeks ago

2 years 15 weeks ago

3 years 12 weeks ago

3 years 36 weeks ago

3 years 36 weeks ago

3 years 38 weeks ago