economics

Can a Tralfamadorian make predictions?

Tue, 31/10/2017 - 07:56 — dan

Tralfamadorians are four-dimensional alien beings able to travel anywhere in time as well as space. Or so Kurt Vonnegut reports, quoting one as saying:

"I am a Tralfamadorian, seeing all time as you might see a stretch of the Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is. Take it moment by moment, and you will find that we are all bugs in amber."

My question for the day: could a Tralfamadorian make predictions? Short answer: yup, totally. Longer answer -->

Our root for the word 'prediction' wouldn't make sense to a native of Tralfamadore. It literally means pre-show - to "say or estimate that (a specified thing) will happen in the future".

This has always seemed a bit odd to me, only half of how we actually use the term. Looking at things from a Tralfamadorian perspective makes this more obvious: the word 'forecast' has no meaning on Tralfamadore. All past and future events are accessible to them. There's no such thing as a Tralfamadorian weather forecast. They don't bet on horse races. They can't try and game the stock market. They can't actually have a stock market.

But they could still make the kind of predictions we consider among the most important: what Gregor Betz calls an `ontological prediction'.*

Here are three famous ontological predictions (one mentioned by Betz). One: the existence of Neptune deduced from oddities in the orbit of Uranus (I see you snickering...). There was either another planet or Newton was wrong. It turned out there was another planet. Then two of Einstein's: light should appear to bend as it passes through gravity-warped space; and the existence of gravity waves. The first was famously (though not uncontroversially; see also this) confirmed by Eddington during an eclipse.** Confirmation of gravity waves is brand spanking new. Immediately, they are cosmically awesome, able to dig deep into the universe to solve the riddle of where some of the heaviest elements like gold come from (neutron stars colliding... whoooaaa).

So - those were all predictions, yes? And each did provide statements on the future - but only kind of by default. The future is the only place we can test our theories. On Tralfamadore, that's not true. Tralfamodorian Einstein could come up with his theories, look up a suitable eclipse in the seventeeth century on his four-dimensional road map, pop over to meet Newton for a bit of co-corroboration, maybe nipping to Papua new Guinea in 1698. (Probably best not to over-think it... wouldn't all Tralfamadorian predictions instantly propagate everywhere/when? So everything would by necessity be known instantly leaving nothing to be discov... oh, they're just a fictional device for making a point, OK then. Phew.)

All of which is a slightly belaboured way of saying: ontological predictions are fundamentally different to forecasts. They are timeless (though the realities they seek don't need to have always existed). They are about seeing things that were already there but we didn't know to look for.

The fact we have to test our ontological predictions in the future doesn't change how different this is to a forecast. It's unfortunate our definitions reinforce the idea that `predict' and `forecast' are the same. Of course, the two are dependent on each other: actual forecasts need underlying theory, and discovering that theory is an ontological-prediction job. But there is conceptual clear blue water between the two of them. New forecasts using an existing method don't require extra ontological prediction. You could also, for instance, improve weather forecasting independently of ontological prediction by throwing more powerful computation at it or some novel refactoring, without making any deeper discoveries about the underlying physics.

Why does this matter? Well, this is all a pre-amble to another post: after reading another attack on a cartoon version of Milton Friedman's argument about model assumptions, I feel like having a proper go at exploring why those (seemingly very popular) arguments miss the point, and why that's important. tl;dr: he never said "assumptions are irrelevant". He did say predictions are the ultimate arbiter - but it's hard to get very far without being clear what prediction actually is.

Once you start digging into this, it also ends up saying something about how different disciplines see themselves, how the public sees them, and how we frame the entire research enterprise in applied versus non-applied terms.

It's also a trope used by many people to reassure themselves that the entire edifice of economics is clearly stupid. That's annoying, wrong and that used to be me. But it's also used by people who should know better to bolster their economics-heretic credentials, and that's especially annoying. So, more at some point before 2019, I hope, or possibly before now if I can find a Tralfamadorian to work with. Thoughts gratefully received in the meantime: does this two-part distinction in prediction scan?

Update: oh, it turns out Friedman was quite explicit about including ontological prediction in his definition: "to avoid confusion, it should perhaps be noted explicitly that the "predictions" by which the validity of a hypothesis is tested need not be about phenomena that have not yet occurred, that is, need not be forecasts of future events; they may be about phenomena that have occurred but observations on which have not yet been made or are not known to the person making the prediction. For example, a hypothesis may imply that such and such must have happened in 1906, given some other known circumstances. If a search of the records reveals that such and such did happen, the prediction is confirmed; if it reveals that such and such did not happen, the prediction is contradicted." Source.

--

* Note Betz also thinks a prediction is a "statement on the future".

** Skipping over gravity having Newtonian effects on light - look, a black hole prediction!) Though if I'm reading that right, it's based on light being a particle with mass.

Humans: nought but shipping containers that need to sleep at night

Mon, 14/03/2016 - 12:06 — dan

On the theme of economic reductionism / turning flesh and blood human beings into cold robot calculators: the central theme running through the PhD and the last project was the effect of distance on economic choices: what people buy, where they buy it from, what/where organisations buy, how they change buying/selling and location together as a single choice set. Which is more-or-less a definition of spatial economics.

One of the ideas that turned out to be very useful for thinking about it is value density. As I use the concept, this is just the ratio of an object's value over 'cost to shift it a unit of distance'. So if it's selling for five pounds and you need to ship it ten miles at fifty pence a mile, its full cost is going to £10 and its value density is ten.

In the usual use of value density, the focus is on weight and bulk. Weight hasn't really been a part of recent spatial economics, even if it's obviously continued to be essential for actual logistics planning. Weber's is the classic work that looks at optimal siting giving inputs, weights and distances - but it's past a hundred years old now and 'proper' spatial economists dismiss it as mere geometry. ('That literature plays no role in our discussion' is all it gets from Fujita/Krugman/Venables.)

But shifting the idea of value density to 'how much it costs to ship per unit of distance' alters this: weight/bulk are important only for how they change that cost. Value density as I'm defining it can also change if, for example, fuel costs go up - which is why the idea ended up being superbly useful. It gets more complex if one starts to factor in time issues (the main reason containerisation transformed the planet was due to its impact on time, not distance) - something that, up to now, I've studiously avoided - so in true quant style, since it's difficult, let's just pretend it doesn't matter for now...)

Value density is a concept that, as far as I can tell, only gets used in the logistics literature - a very applied setting where analysts support decisions about actual production networks. I first heard it mentioned by Steve Sorrell and thought, "wossat then?" Because of this, it doesn't seem to have been used as a 'how do spatial economies work' tool.

It's the 'value' part that makes value density interesting. Because the value of something is determined mostly by its economics, only very minimally by its physical weight/bulk/distance-cost, it can be changed by anything that can add or decrease that value. From a non-spatial point of view, that's trivially obvious: something's real cost drops if, for example, wages rise. But when these two are combined, value density means that changing something's real value also changes how far it can economically be moved. That puts it right at the centre of how spatial economies wire themselves.

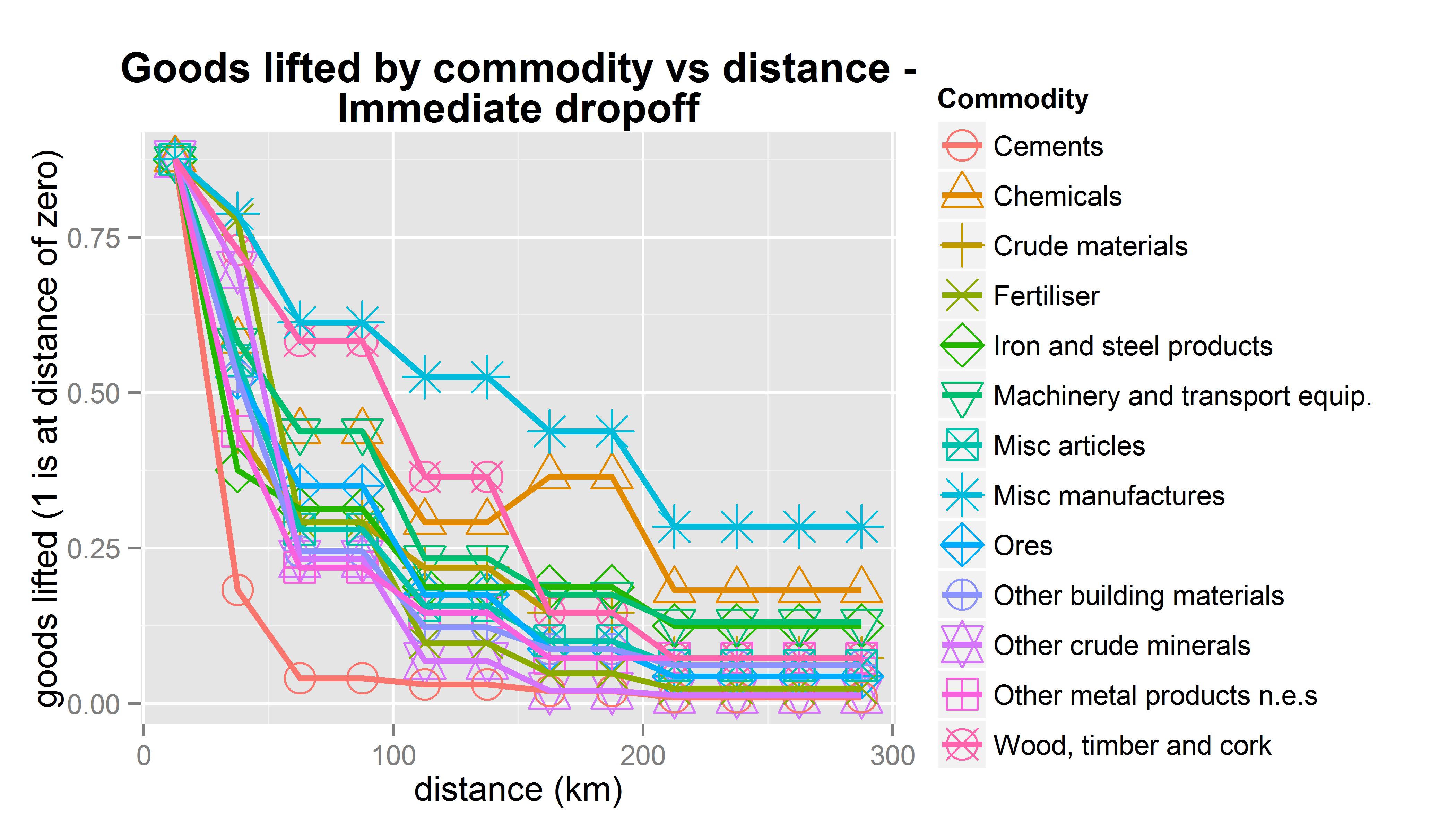

So where Weber cited the weight of certain primary inputs as the reason they don't move very far, logistics folks know that's not it. This can be seen along whole production chains: primary inputs will often need to be close to the first stage of production. At each following stage, more labour is added - and hence more value. Extra value can be added anywhere that extra economies of scale can be squeezed out. This is possibly what determines the dropoff of UK domestic trade (see pics) I dug out of the transport data: low value-density cement, sand, gravel, clay at one end, manufactures at the other (though there are likely plenty of other factors at play, since it's just domestic movement).

This leads to what, for me, seems like a rather startling conclusion: it's the ratio of value to per-unit distance cost, not either alone, that determines the spatial reach of economic networks. This was a very useful idea for the last project as it meant I only needed to determine one number, not two. Again, if we're talking about value versus weight - not a shock, huh? It's when fuel costs or other per-unit distance costs change that it gets interesting. You can increase the spatial reach of your economy by decreasing fuel or time costs - or by increasing value. That can happen through, for example, a more educated workforce with higher wages, through new production methods, through Jacobs-style diversity externalities caused by diversifying clusters - whatever pushes value up.

But there's an exception. There's one input into the production process, one feedstock into the great grinding millstone of the economy, that doesn't quite work in the same way. Human beings. Superb quote:

Humans remain the containers for shipping complex uncodifiable information. The time costs of shipping these containers is on the rise because of congestion on the roads and in the airports while the financial costs of so doing are also rising due to increases in real wages of knowledge workers who are the human containers. (Leamer/Storper, the Economic Geography of the Internet Age, Journal of Intl Business Studies, 2001 p.648).

So humans can be value dense, just like anything else you shift on a truck and back into a factory. But, as production inputs, they have some idiosyncracies that set them apart from coal or crankshafts or hard drives. At the top of the list: with some exceptions (i.e. people who don't stay in one place) they all need to be within a few hours' radius of the place they input their labour. They also have a range of other functions - some of them not even economic! - that determine their spatial patterning. A whole range of essential inputs, for instance, are required to guarantee creation of the next generation of shipping containers for complex uncodifiable information.

Putting aside my flippancy, this is sort of car-crash fascinating to me. It is actually possible to see a quite generalisable theory of value density that just includes some of these tweaks to humans. After all, there's nothing novel about the approach: humans are one side of the most commonly-used production economics idea, the Cobb-Douglas, with capital on one side and labour the other. And we've mostly become blithe to the presence of 'human resource' teams in all large workplaces. But this is a little more specifically economising, isn't it? Not only labour, but an input with certain ratio of value to per-unit distance cost, just with the addition of some tweaks.

I think it works though. That's the marvelous thing. It's this fundamental difference - something explored in detail by Glaeser, for example - that is determining the shape of modern cities. Decreasing distance costs, either relatively through increasing value or otherwise, increases the value density of us lot.

What I'm still not clear on, and why I'm writing all this down: we know that theories change reality. I go on about that all the time. They also change how we see the world individually - obiously, really. Even if there was some clean way of separating out my analysis of how society's structured from my daily world-view, how would that make sense? Don't we try and learn about the world specifically to change how we see it, both as people and collectively?

So I find myself asking the Dr Malcolm question ('Yeah, yeah, but your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn't stop to think if they should'). Not because, of course, it'll actually make me turn off the computer and walk away. At least not yet. But I do wonder - the kind of reductionism I've just laid out might produce genuine insights, but at what cost? I've been wibbling recently about the inseparable link between language networks/production, and this stuff is just another version of that. The cosmology of economics creates some kind of productive landscape - but is it one we want? Should I be comfortable in promoting the use of that language, justifying it with claims that simplifying produces useful views of reality?

---

New year's earnestness 6/17. If Eddie Izzard's having to do two marathons on his last day, I should be able to catch up on the blog target in eight weeks, right? Hmm.

How to avoid comparing rich and poor

Fri, 08/01/2016 - 18:51 — dan

Reading Mark Blaug on Pareto efficiency was a lightbulb moment. As he says, Pareto's idea was a 'watershed moment' in arguments about utility. From a distance, the outcome can seem pretty meaningless but it's an important political fork in the road - and one that shines a light on how the abstractions of economic theory get tangled with power politics. There's a story about Pareto himself to be told, too - I'm not going into that. This is about where his idea went after that.

Benthamite utilitarianism hadn't been going badly. But it was premised on the idea that different people's well-being could be compared - after all, there's no other way of knowing if you're increasing or decreasing the general welfare.

This seemed intuitively straightforward at the time. But, perhaps as the study of utility as an economic concept developed, that began to change. Attempts to actually track down a scientific measurement of people's utility got underway. Folks got upset about the obvious problems in trying to define what utility really was.

Pareto offered a way out of this. I'd known the concept before but not understood its significance until reading Blaug. Pareto efficiency: you've reached an optimal state when it's not possible to make anyone better off without making someone else worse off. Sounds innocuous enough. But notice that it sidesteps comparability. As Blaug says:

"The beauty of Pareto’s definition of a welfare maximum was precisely that it defined the optimum as one which meets with unanimous approval because it does not involve conflicting welfare changes."

It rules out the possibility that one could -

" - evaluate changes in welfare that do make some people better off but also make other people worse off" (Blaug / economic theory in retrospect/ 1997 p.573-4).

So it can say absolutely nothing about inequality. Or rather, it implicitly says that it doesn't matter: you cannot, for example, assess whether taking money from one person and giving it to someone else will improve welfare overall. Bentham schmentham.

Pareto optimality, unsurprisingly, became very popular and is essential to most general equilibrium models. I don't understand those - I'm only familiar with Krugman's spatial GE stuff, which is not the same (they're driven by explicit utility differences across space). But I'm not surprised models that, by default, exclude inter-personal comparisons should form the inner sanctum of modern economics. A model that can, by design, exclude any discussion of redistribution was always going to thrive.

Which is not to say there aren't plenty of approaches that do analyse the differences between rich and poor. But... and I'm not on solid ground with this point at all... the kind of economics that sits in rooms with ruling elites don't generally use those.

I want to make two little points about this. The first comes from having actually used utility as a concept in my modelling work and found it extremely valuable. I spent far too long listening to the siren-calls of agent modellers telling me to go towards 'realism', then in the process of slowly solving my problems, realising I had ended up back at basic micro-economics.

So first: if you're going to use utility at all, you'd better accept it's a silly idea that lets you do useful things. People are not actually utility maximisers, but the concept is a superbly effective way of thinking about how people react to cost changes in certain situations. (This is all very Friedman [pdf].)

So all that pursuit of the actual foundations of utility in our meat-brains is, somewhat, beside the point. Given that, we should use the idea in ways that are useful. Ruling out utility comparisons is just a little bit too convenient a result, politically. There isn't really any reason to, and the angst about utility's epistemological status makes about as much sense as rejecting traffic models because they don't use gravity equations. (Er, at least I think they don't...)

Second, one of the most powerful ideas that utility gives us is diminishing returns. It's easy to forget how much of a puzzle this was - the whole water/diamond problem thing. It should be blatantly obvious to anyone who thinks for a few seconds that money itself has diminishing returns. Say a 7% drop in income forces your family to eat less well and you to have to skip meals sometimes. It shouldn't be beyond our economic theory to see this as more severe than having to compromise on the Land Rover you had your eye on by buying a Mondeo.

This is kind of paragraph that sets the flying monkeys off, though. Particularly since the 2008 crash, particularly in the UK - the story that's been slowly pushed through all media channels is solidifying into political reality: such talk is the politics of envy, rather than - as it actually is - a perfectly sensible way to think about wealth.

These days I generally end up thinking "it's all about the middle way". The same applies here - effective economic comparability could imply deep intrusion in people's lives, the state charged with measuring and judging what forms of spending were more worthy than others, creating a kind of state-sanctioned Maslow hierarchy. But it doesn't need to - if one is capable of accepting the basic premise that severe poverty makes people's valuation of money much higher than for richer folk, it just implies the need for policies that reduce inequality.

And there isn't necessarily anything wrong with Pareto efficiency. The problem here is what happens when powerful abstract ideas interact with powerful political forces. Things get warped to Wizard of Oz proportions. Other perfectly sensible ideas can't get their shoe in the door. But it's foolish to use Pareto efficiency to exclude distribution thinking, just as it would be idiotic to ban its use because it was too right-wing.

I wouldn't want to live in a world where political schools had their own paid-for economic theorists. I do still believe in the pursuit of actual social-scientific truths. But Pareto efficiency is one of those ideas that hammers home just how hard it is to pull economics and politics apart.

The point: as far as possible, your economic/mathematical models shouldn't rule out one particular political way of thinking. The choice of how we balance wealth in society - that's a political issue. There's no easy way to keep an unbreachable line between positive and normative - modelling methods will always interact with our political assumptions and power structures in sometimes very-hard-to-see ways. And I also believe in the power of quant modelling to help us understand which things may not work if pursuing certain political aims. But modelling distribution issues - and using utility to do this - no more makes you a communist than using Pareto efficiency makes you a fascist.

(p.s. googling Pareto inequality reminds me there's a mountain of stuff on this subject I don't know. But if I think like that all the time, I won't get a single blog entry written, let alone seventeen...!)

------

New year's earnestness 1/17

Equilibrium schmequil-schmibrium

Thu, 13/02/2014 - 20:39 — danA comment by `Zamfir' at crooked timber (via Krugman) jumped out at me:

Lots of mechanics and other physical processes are modelled as equilibria, or quasi equilibria, even when people know that it is not correct. That's typically the opposite of purity-obsessed scholastism, it's more an engineering fix to get bad results that are still better than no results. You multiply the results by an out-of-the-blue correction factor for `dynamical effects', and hope for the best.

Contrast with Philip Ball:

[Economic] models take no account of real human behaviour, which is far too messy to permit any theorems that can be proved rigorously. Economic models become citadels of crystalline mathematical perfection that would shatter if touched by the harsh rays of reality.

(He does immediately go on to say "it would be grossly unfair to suggest that this describes everything that happens in economics, let alone in all social sciences... But it is widespread".)

His target isn't specifically the use of static equilibrium assumptions in economic models, but the view Ball gives is spot on for how most agent-based modellers and complexity thinkers view it. ABM and complexity are seen as "a pioneering break from a moribund Newtonian worldview" (Manson 2001 p.412), obviously superior to those silly static equilibria. Usually they will argue that's the case because it's `more realistic'. Hmm - so's Call of Duty 4, I'm not sure that makes it a better model of anything.

Slightly less flippantly: the models are never the problem. You try what you can and throw it at the wall of reality. Some things stick. Or, as Einstein put it, talking about physics: it's

"a logical system of thought which is in a state of evolution, whose basis cannot be distilled, as it were, from experience by an inductive method, but can only be arrived at by free invention. The justification (truth content) of the system rests in the verification of the derived propositions by sense experiences. The skeptic will say: `it may well be true that this system of equations is reasonable from a logical standpoint. But it does not prove that it corresponds to nature'. You are right, dear skeptic. Experience alone can decide on truth." (Quoted in Kaldor 1972 p.1239.)

Like I say: try what you can, throw it at reality. I'm not saying I'm any good at this - I have a definite tendency to prefer making little pretend worlds - but the point is, there's nothing intrinsically wrong with using static equilibrium as an assumption. Zamfir's quote made me happy thinking about it being used in a practical manner all over the place. In some situations it's useful, in others less so, in some it makes no sense at all. The point is how it's used (already rambled about that at some length).

I have this notion there's a direct parallel to `emergence' in agent modelling. ABM is all about interaction: that's its basic structure and its main strength. The use of physics ideas in classical economics is its strength, but it's also what makes it brittle. The same is true for ABM. To be useful, you want your method to be able to help examine any number of different questions - but in ABM, it's easy to end up defaulting to Epstein's `if you didn’t grow it, you didn’t explain it' (Epstein 2006 p.xii) and thinking you've answered something. Di Paolo and Bullock nail that one: conflating emergence and explanation means whatever you were wanting to look at has been `brushed under the carpet of emergence' (Di Paolo et al. 2000 p.8).

This is somewhat reminiscent of the final deathstar scene in Return of the Jedi: ABM ends up nearly becoming the thing it hates most: wedded to an obsession with realism, it can no longer experiment or pursue a diverse range of questions. Actually, that didn't sound anything like Return of the Jedi.

Oh good, another P3 short essay on economic models

Sat, 04/08/2012 - 11:07 — danWell, as long as it keeps on tricking me into writing shit down, I'll keep on unashamedly writing stupidly long comments no-one in their right mind would wade through and posting them here. Makes me feel like I'm keeping busy! That said, in a zero-sum world where I could be writing papers or blathering on blogs, I wonder which I should be doing...?

---

We've got into discussions on P3 before, here and here, though not really coming to any conclusions. But you'll see we've picked up on a fair few things you've mentioned - one of my bugbears being the misuse of Friedman's 'F-twist' argument, claiming he says "unrealistic assumptions don't matter" (something I also repeated until, looking for ways to think about model-building, I actually read what Friedman said, which is subtly but vitally different to the caricature so often used to paint economists as naive Vulcan-like imbeciles.) A lot of that's come from my (still not quite finished!) thesis work; I've stuck the current version of the navel-gazing model chapter here. There's a lot of overlap, even many of the same quotes, with things your blog's discussing.

The most recent article of yours shares some of the same view of modelling in general. I'm not sure whether this eco-economics attack on modelling stems from quite the same source as MT's skepticism, would be interested to dig more into that. I think this starts getting close to the heart of this, which again comes down to what we're claiming models are *for* (which I waffle on about interterminably in that thesis chapter.) You quote the Daly/Solow argument (Daly: "If we want a bigger cake, the cook simply stirs faster in a bigger bowl and cooks the empty bowl in a bigger oven that somehow heats itself.") But you don't provide Solow's response; quoting meself quoting Solow:

"Solow's reply to this highlights a recurring argument used to defend the abstract nature of many economic models - critics are taking them too literally, and not considering how the models are used: 'We were trying to think about an interesting and important question: how much of a drag on future growth, or even on the sustainability of current production, might be exercised by the limited availability of natural resources and the inputs they provide? ... The role of theory is to explore what logic and simple assumptions can tell us about what data to look for and how to interpret them in connection with the question asked' (Solow 1997 p.267/8). Solow goes on to point out that the argument should be about how substitutable renewable and non-renewable resources are, given that the former are likely to be highly capital-intensive. (Ibid.) He appears to be saying that his critics have mistaken economists' models for their actual understanding of the world, rather than tools that aid that understanding."

Which is what I was arguing Krugman also says in the comment above, and what Friedman was saying way back in the 50s (though whether Friedman follows his own advice, I'm not qualified to say - I only really know his stuff from his 'essays on positive economics'). E.g.: when assuming s = 1/2gt^2, "under a wide range of circumstances, bodies that fall in the atmosphere behave *as if* they were falling in a vacuum. In the language so common in economics this would be rapidly translated into: the formula assumes a vacuum. Yet it clearly does no such thing."

And of course there are plenty of circumstances where it would be a completely inappropriate way to think about falling objects. But that doesn't make using it 'naive' or invalid, any more than using temperature and pressure measurements does (when we know that at atomic reality is more complex).

I haven't got to the bottom of this stuff to my own satisfaction at all. It would be great if we could carry on exploring them here at P3, but I wonder if that might require some kind of agenda!? I wouldn't mind starting with actually working up a common understanding of some economic models as they are. Stephen, it sounds like you have a solid economic background. I don't really; I've gone off and done this by myself while my supervisors looked on horrified, and found it immensely tricky to find economists to check my understanding with (perhaps my own networking failings, I shan't blame economists' closed-shop attitude!)

Some suggested things to discuss: understanding a basic general equilibrium model, how they've been used, how they're related (or not) to the actual policy workhorse DSGE models, what other models inform policy; whether economic training in these models is (as Krugman's own view seems to suggest) more a set of shared heuristics almost incidental to how economists are apprenticed in a policy episteme - so it's not 'about the truth of the models' so much about training and embedding policymakers. Which would mean we could attack the models til the cows come home and we'd be missing the point. You can actually see how that might function in a completely different context: Lansing's work on Balinese rice management, where a shared collective model allows autonomous ritual actions to both re-create the landscape and manage water to maximise crops/minimise pests across the Subaks. There's no 'correct' top-down model, there's a shared social technology tied into a specific landscape, kept alive in people's minds through ritual. Lansing calls it 'sociogenesis': "when Balinese society sees itself reflected in a humanised nature, a natural world transformed by the efforts of previous generations, it sees a pattern of interlocking cycles that mimic these cycles of nature" (priests and programmers p.133). Mainstream economics may partly work the same (esp. ritual!) but on quite a different scale (and of course with the open question of whether it's capable of ending in a cyclical self-maintenance or is instead a global virus; cf. Agent Smith).

It'd be good to explore a recent-history example of an economic model's impact: Krugman's core model again. Since 1991 it's gone from 'thought experiment to lure economists into thinking about geographical questions' (while also radically changing the profession's view of the central dynamics of international trade) to a World Bank report on geography coming straight from it, despite Krugman's own apparent caution on using it - and a continued suspicious lack of empirical support that shouldn't be a surprise given it was only ever meant as a toy model to make a point. (I've never quite understood what Krugman's own view of this is; initially caution and a notable silence as the Nobel prize arrived and some of the key ideas got absorbed by the body politic. But I'm sure he'd have some clear Views on it.)

And to ask the same question again: given all this, what role do we actually think models can / should play in both analysing and organising society? I have a book in front of me by Stan Openshaw, an ex-professor from my department, called "Using models in planning" (1978). A quote:

"Without any formal guidance many planners who use models have developed a view of modelling which is the most convenient to their purpose. When judged against academic standards, the results are often misleading, sometimes fraudulent, and occasionally criminal. However, many academic models and perspectives of modelling when assessed against planning realities are often irrelevant. Many of these problems result from widespread, fundamental misunderstandings as to how models are used and should be used in planning."

While he's writing about town planners, the same applies. We don't really understand how this is meant to work. It happens anyway, but without asking about this, we're stuck in this strange place where one side carry on using their models while others keep on going "ha! look at those stupid assumptions!" - as if by some miracle of alchemy, the models being criticsed will crumble like vampires at dawn. Kuhn's stuff makes clear it doesn't even quite work like that in the physical sciences: the relationship between discovering problems, errors, better models and the structure of a discipline is way more complex. If that discipline is then tangled into political power, there's a whole other bunch of stuff going on...

What are costs, actually? (Another P3 comment...)

Thu, 17/05/2012 - 17:59 — danAnother comment at P3, responding to MT.

Me: "Economics is the study of how people react to cost changes." Hmm, you're right - I need to be more careful with nomenclature myself. I'm sure some of the heterodox econs would say the term is 'essentially contested'. Thinking about it, though, I think my def still works: economics concerns itself with the costs and benefits involved in human choices. I don't see that Marshall's questions contradict that: everything from how we structure institutions, what sectors should be state-owned, the ethics of wealth distribution - is all covered.

"presuming you mean 'cost' in the colloquial sense of money". No, absolutely not. The magic washing machine is a pretty perfect example: what are the costs/benefits of how we use our time? How does technology and societal structure alter that? Rosling very cleverly illustrates precisely this point by pulling books out of the washing machine: it's a machine that produces women's education as well as clean clothes. I see no problem in thinking about time this way while also thinking about how time is socially constructed (see this classic E.P.Thompson article, PDF) and how economic definitions themselves may alter us.

The transition from a mostly agricultural society to what we have today can be thought of in the same way. Two things have happened simultaneously: agri technology has improved, meaning waaay less people can produce massively more (put aside for now 'but it's all just eating fossil fuels'...) The rest of the economy has grown in a feedback process: enabling both increased agri output and freeing up people's time to work elsewhere. As a result, we've also seen a massive morphology change as food processing has moved out of the household/community and into today's sophisticated global industrial networks. A key part of that is how people value their time: we could all be growing food in community gardens and cooking it at home. We have the time to do that. Mostly, we don't. Why not? We prefer to work in paid jobs and access relatively cheaper food, as well as a set of other things we like. Computers, electricity, transport, beer, time to sit and stare at the wall...

Again, there's a whig history danger here: it was meant to be thus, and is natural and good (while forgetting small matters like kicking people off their land when sheep became more profitable, much as we're doing now because car-food is more profitable than people-food [my blog] in many places). But there's also a lot of value in thinking about these changes through the prism of how we value the costs and benefits of our time.

I've found myself looking at my own 'revealed preference' and changing my views. I used to be a lot more fervent about local food growing, until I realised what my shopping habits were telling me: I actually prefer to earn a living in academia and spend time I'd be putting into agriculture on other things, like commenting at P3. If other people feel differently, fine. But I don't think the existence of supermarkets is necessarily a sign of collective moral failure. I also reserve the right to a) reflect on that and change in the future but b) not to have anyone else actually force me to change, unless I've taken part in a democratic process to enforce it ->

Cos maybe supermarket are evil, and individually we're too vulnerable. Marshall lists this in his questions: "what are the proper relations of individual and collective action in a stage of civilization such as ours? How far ought voluntary association in its various forms, old and new, to be left to supply collective action for those purposes for which such action has special advantages?" In the case of supermarkets - and some other market structures - perhaps we should not trust the emergent result of all our collective value-judgements. Instead, maybe we need to get together and decide a set of constraining rules: those we agree are needed, but that we recognise individual actions will tend to corrode over time. That would be democracy. It's also why people who claim that money represents the zenith of democracy [me again] are talking nonsense. If individually we are incapable of making the right carbon choices, collectively we can decide to restrict our choice set.

Marshall's questions

Fri, 08/07/2011 - 11:22 — danFrom one of the founders of modern economics. From p.114 in the physical book (1895) which I'm sure the library shouldn't let me take out - it's an antique! It's got errata pasted in by hand. Online here. The first three paras are quite dry, but give a good outline of the full meaning of 'general' analysis in economics. As far as I can tell, we're some way from knowing all the answers, especially as regards the general effect of - say - energy cost changes. It picks up at para four, 'How should we act so as to increase the good and diminish the evil influences of economic freedom?' Later, 'taking it for granted that a more equal distribution of wealth is to be desired...', ho ho, how quaint!

If the government restructured the laws of physics...

Sat, 13/03/2010 - 12:04 — danA commenter over at Tamino's blog puts in a good word for economists:

How would you physicists like it if you had to survey a bunch of molecules to find out what they planned to do, only to have most of them change their minds anyway, and the government restructure the laws of physics because of some opinion poll?

Price waffle

Wed, 14/05/2008 - 09:31 — danI caught a programme last night on the beeb about property. Nothing new there - you can be guaranteed to find a property programme of some description 50% of the time the telly goes on: if the schedulers are to be believed, we're obsessed. (Indeed, there was another property prog on Channel 4 at the same time.)

But this one was a little more thoughtful. The last person to be interviewed was an estate agent based in Sandbanks, Poole - not too far away from where I used to live in Bournemouth. A few years back, one place sold for a particularly large amount of money, and worked out at something like £900 per square foot. This particular estate agent did a quick calculation and discovered this made it the fourth most expensive place to live in the world. The next step is brilliant: he then trumpeted the whole area as such. 'Sandbanks: the fourth most expensive place to live in the world!' Thus began Sandbank's insane rocketing into the property stratosphere, accompanied (as he notes) by developing new offices and a whole selling style suitable to people wanting to buy into the Sandbanks glow.

Impact of the minimum wage: how hard can it be?

Mon, 12/05/2008 - 11:02 — danOver at Crooked Timber, there's a great post on the minimum wage where Kathy argues that 1) there are plenty of empirical reasons why increasing a minimum wage may not lead to higher unemployment and 2) that you'll get into trouble with the economic 'fundamentalists' if you try and work on this issue without concluding that it does.

Recent comments

21 weeks 6 days ago

2 years 12 weeks ago

2 years 12 weeks ago

2 years 14 weeks ago

2 years 15 weeks ago

2 years 15 weeks ago

3 years 12 weeks ago

3 years 36 weeks ago

3 years 36 weeks ago

3 years 38 weeks ago