3 stars

Economics: reform or revolution?

Fri, 05/01/2018 - 18:41 — danDigging into economic arguments around austerity has been like accidentally walking in on a pub brawl: honky-tonk piano still playing, people being hit with chairs, others thrown the full length of the bar breaking all the glasses, someone thrown through the first floor balcony etc. Nobody gets this worked up about spatial economics.

I've been doing this digging since this little fantasy post about the idea of making austerity economics more visible (or, rather, making macroeconomics more visible, and so arguments about austerity more transparent). It's been a dream for a long while, probably since first discovering the MONIAC machine, the (currently not working) prototype of which sits in Leeds University's Business School foyer.

I've taken a few baby steps in that direction1 - it may never come to anything, but the process of attempting it has churned up a whole load of economics stuff I haven't thought about in a long time.

I've found myself flummoxed by some of the things I'm seeing in the bar brawl. Exhibit A: Steve Keen's cartoon - taking the CON out of eCONomics! - from which we learn, apparently, that Krugman and Summers "don't know what they're talking about". Blam! Thwack! Keen's mode of operation may be extreme in heterodox circles but it seems to be wildly popular.

I've also just got a copy of James Kwak's 'Economism': so far, this has been a much more measured book with very little I disagree with. It acknowledges the power of economic thinking - but it paints a convincing picture of "economics 101 as ideology", captured and promoted by particular elites, turned into a propaganda tool. On my first skim, it doesn't recommend smashing everything to bits, but instead changing institutions, expanding and re-weighting curricula.

As it points out, the emergence of 'economism' can be seen just in how topics were re-ordered over time in Samuelson's textbook. It quotes a THES article...

"Economics degrees are highly mathematical, adopt a single narrow perspective and put little emphasis on historical context, critical thinking or real-world applications."2

...but notes that, once one gets past this highly standardised economics (largely harmonised with ideological economism), actually, there is a great deal of much more subtle economic thinking going on. It's just that students aren't initially exposed to it.

I don't know how true that is - I suspect economism of the sort pushed by Paul Ryan when he's showing woefully simplistic supply/demand curves to justify dismantling Obamacare (an example from the book) has a messier relationship to taught econ101. But the book's central claim - that there is a version of economics used as an ideological battering ram - is hard to argue with.

Self-indulgent background follows for several paragraphs... I'm in an odd, sort of lucky, sort of rubbish, situation: for the PhD model (finished 5 years ago now, oi...) I found some economic ideas incredibly useful. While I'm still pretty insecure on my views about this (it was just me in a dark room building a model for years and those ideas remain largely untested) I perhaps got a unique perspective, being forced through trial and error into finding how useful economic ideas can be, rather than having to learn and regurgitate the orthodox package.

I got to jump off the rails and go wandering freely. The model itself forced me to think critically and historically - I ended up running about randomly on the economic landscape, solely on the look-out for ideas that could move the model forward.

There were no stakes (besides me finishing the ****ing thing): I just found micro-economics really useful for modelling how people and firms react to cost changes if they're embedded in space, and that agent modellers' claims to better "realism" made no sense in isolation.

When it comes to austerity and macro-economics, obviously the stakes get a lot heavier - and much more ideological. Black-hole gravity wells of ideology can warp even the purest scientific disciplines so it's unsurprising what a mess it makes of economics.

Before the PhD, I started off with the same worldview as many heterodox economists. I'd studied politics at Sheffield and fully took on board the standard, incredulous dismissal of homo economicus, the perfectly rational calculating machine: insultingly reductionist, logically absurd (Friedman's "realism of assumptions don't matter" line, a caricature of his actual argument, would exemplify that idea) and nothing more than a figleaf covering the goolies of power.

I found the strongest confirmation of this in World Bank reports studied in my final year. One of them claimed the goal in developing countries should be to "supplant or amend" (change or die!) all "behavioural norms" that were "market dysfunctional" and replace them with the market-functional versions. It contained an entire "tactical sequencing" plan (divide and conquer!) to overcome state and societal resistance to this supplant/amend plan.

It looked for all the world like a strategy for creating homo economicus, for transforming entire states to achieve this. It's easy to assume reports like this reflect the Sauron-like power of neoliberalism, rather than just whatever the writer happened to think that day (as well as being just confirmation bias). But it does support the 'Economism' idea: global market norms are pushed by powerful organisations. And economics is the theoretical branch of that push.

On the academic side, you can also see how methods become shibboleths. As Krugman says, his geography ideas needed to be expressed as a general equilibrium model to be accepted:

"Mainstream economics isn’t going away: like it or not, the White House has a Council of Economic Advisers, not a Council of Geographical Advisers, the World Bank hires lots of economists and not many geographers."

The World Bank and other organisations have worked to recreate this same structure, including setting up and staffing finance ministries around the globe. (Says 2002 me - 2018 me replies, "well, did that happen and how successful was it?" I don't know. I do know trying to implement such plans always tangles with messy reality in unexpected ways. And that the World Bank has radically changed since then...?)

So while I kept to my little dark room, building spatial economic models, I found basic economic modelling ideas really really useful. But beyond that, in the bar brawl of macroeconomics, things get a lot messier - there really is global power, propaganda, economism to contend with.

Being simplistic, I can imagine two heterodox ways to think about that reality: revolutionaries and reformers. Where Keen might be a revolutionary, Kwak is more of a reformer (he's clear about that in this blog post). The revolutionaries won't be happy until the Great Neoclassical Tower of Barad-dur has come crashing down, having thrown the... err... Ring of Microeconomics? Into the lava of Mount Marginal?

That's not a political mapping: these revolutionaries are not necessarily more leftie. It's just that they want to throw the theoretical baby out with the ideological bathwater. I get the sense my idealistic notion of creating a clearing for transparent discussion of macro method just wouldn't work for some of those folks. (There may be some also who object to quant modelling generally - I'm saving that for another post.)

And the fact that it's wildly popular does worry me. I wonder if these attacks aren't playing the same ideological game, just as awash with shibboleths as their target. It doesn't seem like a way forward to me, if we really want to develop methods and institutions that can actually manage national economies well, or even - crazy idea I know - maintain a functioning biosphere.

Whether the actual visualisations ever happen - definitely still in the realm of fantasy but I am trying little baby steps! - there's a lot else to think about here. Stuff about realism in particular, about how different methods should be valued or discarded, seems essential to me. I still haven't really clearly explained why.

Also, more careful thought needed on how this all connects to economism. I keep on defending that one chapter by Friedman because I found it really useful at a critical moment - yet he's also a central figure in the creation of economism as an ideology, it seems. Can these two halves in my brain be reconciled?

But the fantasy idea is still appealing: arguing the case about the actual economic method in as transparent a way as possible, using visualisation, models with methods all arguable and clear via github, without diminishing the importance of the political economy. Dream on...

-

I've also been upping the necessary tech skills - it turned out jumping straight into an online macroeconomics sim was bit much so I'm practicing on house prices; unfinished prototype is going well - those numbers are wage multiples, slider is 1997 to 2016. ↩

-

James Kwak, Economism, p.188 ↩

Can a Tralfamadorian make predictions?

Tue, 31/10/2017 - 07:56 — dan

Tralfamadorians are four-dimensional alien beings able to travel anywhere in time as well as space. Or so Kurt Vonnegut reports, quoting one as saying:

"I am a Tralfamadorian, seeing all time as you might see a stretch of the Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is. Take it moment by moment, and you will find that we are all bugs in amber."

My question for the day: could a Tralfamadorian make predictions? Short answer: yup, totally. Longer answer -->

Our root for the word 'prediction' wouldn't make sense to a native of Tralfamadore. It literally means pre-show - to "say or estimate that (a specified thing) will happen in the future".

This has always seemed a bit odd to me, only half of how we actually use the term. Looking at things from a Tralfamadorian perspective makes this more obvious: the word 'forecast' has no meaning on Tralfamadore. All past and future events are accessible to them. There's no such thing as a Tralfamadorian weather forecast. They don't bet on horse races. They can't try and game the stock market. They can't actually have a stock market.

But they could still make the kind of predictions we consider among the most important: what Gregor Betz calls an `ontological prediction'.*

Here are three famous ontological predictions (one mentioned by Betz). One: the existence of Neptune deduced from oddities in the orbit of Uranus (I see you snickering...). There was either another planet or Newton was wrong. It turned out there was another planet. Then two of Einstein's: light should appear to bend as it passes through gravity-warped space; and the existence of gravity waves. The first was famously (though not uncontroversially; see also this) confirmed by Eddington during an eclipse.** Confirmation of gravity waves is brand spanking new. Immediately, they are cosmically awesome, able to dig deep into the universe to solve the riddle of where some of the heaviest elements like gold come from (neutron stars colliding... whoooaaa).

So - those were all predictions, yes? And each did provide statements on the future - but only kind of by default. The future is the only place we can test our theories. On Tralfamadore, that's not true. Tralfamodorian Einstein could come up with his theories, look up a suitable eclipse in the seventeeth century on his four-dimensional road map, pop over to meet Newton for a bit of co-corroboration, maybe nipping to Papua new Guinea in 1698. (Probably best not to over-think it... wouldn't all Tralfamadorian predictions instantly propagate everywhere/when? So everything would by necessity be known instantly leaving nothing to be discov... oh, they're just a fictional device for making a point, OK then. Phew.)

All of which is a slightly belaboured way of saying: ontological predictions are fundamentally different to forecasts. They are timeless (though the realities they seek don't need to have always existed). They are about seeing things that were already there but we didn't know to look for.

The fact we have to test our ontological predictions in the future doesn't change how different this is to a forecast. It's unfortunate our definitions reinforce the idea that `predict' and `forecast' are the same. Of course, the two are dependent on each other: actual forecasts need underlying theory, and discovering that theory is an ontological-prediction job. But there is conceptual clear blue water between the two of them. New forecasts using an existing method don't require extra ontological prediction. You could also, for instance, improve weather forecasting independently of ontological prediction by throwing more powerful computation at it or some novel refactoring, without making any deeper discoveries about the underlying physics.

Why does this matter? Well, this is all a pre-amble to another post: after reading another attack on a cartoon version of Milton Friedman's argument about model assumptions, I feel like having a proper go at exploring why those (seemingly very popular) arguments miss the point, and why that's important. tl;dr: he never said "assumptions are irrelevant". He did say predictions are the ultimate arbiter - but it's hard to get very far without being clear what prediction actually is.

Once you start digging into this, it also ends up saying something about how different disciplines see themselves, how the public sees them, and how we frame the entire research enterprise in applied versus non-applied terms.

It's also a trope used by many people to reassure themselves that the entire edifice of economics is clearly stupid. That's annoying, wrong and that used to be me. But it's also used by people who should know better to bolster their economics-heretic credentials, and that's especially annoying. So, more at some point before 2019, I hope, or possibly before now if I can find a Tralfamadorian to work with. Thoughts gratefully received in the meantime: does this two-part distinction in prediction scan?

Update: oh, it turns out Friedman was quite explicit about including ontological prediction in his definition: "to avoid confusion, it should perhaps be noted explicitly that the "predictions" by which the validity of a hypothesis is tested need not be about phenomena that have not yet occurred, that is, need not be forecasts of future events; they may be about phenomena that have occurred but observations on which have not yet been made or are not known to the person making the prediction. For example, a hypothesis may imply that such and such must have happened in 1906, given some other known circumstances. If a search of the records reveals that such and such did happen, the prediction is confirmed; if it reveals that such and such did not happen, the prediction is contradicted." Source.

--

* Note Betz also thinks a prediction is a "statement on the future".

** Skipping over gravity having Newtonian effects on light - look, a black hole prediction!) Though if I'm reading that right, it's based on light being a particle with mass.

Don't cling to a mistake just because you have spent a lot of time making it

Sun, 30/07/2017 - 21:13 — dan"The chances of the government admitting that austerity has been a failure are precisely zero. That would mean telling voters that all the sacrifices since 2010 had been in vain." (Larry Elliott)

"Don't cling to a mistake just because you have spent a lot of time making it." (Banksy)

There's a school of thought that says ideas are like Soufflés - if you don't give them just the right care when you're baking them, letting the scaffold form as it should, they collapse in a gooey mess. I used to bake a lot of this kind of thing. I didn't get better, I just stopped trying - too ashamed of all the sad little sticky puddings. But I figure I'm a bit older and, if not wiser, more cautious now. Just throw some stuff out there, poke things a bit and see what happens. Do the thing and all that. Nothing may come of any of it, but then nothing will come of nothing if nothing's all that's done. Profound. So that said...

I've got this notion that it should be possible to show how the economy works in a way that's both robust and accessible. I don't mean accessible just from a three minute glance, infographics-style. But it should be possible - for example - to drag otherwise murky arguments about austerity out into the light where you can test views based on what's actually known, obvious, possible. You'd aim for reducing the range of ambiguity to something much less overwhelming. Expanding the little pool of clarity into something much more vivid.

The reason this draws me in is pretty simple: the 'sacrifices' Larry Elliott talks about - they're almost impossible to grasp. The things that have happened, are happening right now, to people, institutions, all apparently to right a listing economy - there seems to be a very strong case this was all totally unnecessary, literally counter-productive and utterly wrong-headed. And the arguments aren't all that abstruse - it shouldn't be that hard to mark out their boundaries. (Hah - note that for later.)

I'm not naïvely imagining there's some process of alchemy that can transform how the austerity debate is seen (or macro more generally). There's a whole bunch of people that are obviously inaccessible to what I'm talking about, not least those ideologically opposed to the idea of any state action who've seen the crisis as an opportunity. They'll continue to push whatever sophistry furthers that aim, of course. There are also people on both sides who Just Know and nothing could possibly convince them otherwise. (I like to pretend I'm not one of those, though don't we all?) Others won't have anything to do with quant of any kind, especially economics-plus-quant: for them, it's an elite-wielded tool propping up power. That's one to come back to - I have some sympathy for this but it's confusing the tool and the user.

That leaves a whole swathe of people who can meet and converse, given the right space and tools. Have no truck with the convenient lie about post-truth. The global response to Trump pulling out of the Paris Accord shows it's the idea of post-truth that's the danger - something well understood by regimes like Russia. (Paul Mason nails this brilliantly in his stage take on 'why it's kicking off everywhere'.)

I'm not saying there are always right or wrong economic answers, but you should be able to set out what the spread of rightywrongyness looks like. And if I'm talking about a tool, this would mean transparency in how it's built too. Code would need to be accessible, assumptions up-front, well commented and explained. The way models are perceived (even by many modellers) leaves a lot to be desired - I'd see this kind of open process as a chance to talk about that as well. It couldn't be something you went away for years to build - the building process itself would need to be a conversation. It couldn't be - initially at least - some single overarching model (h/t Jon Minton).

But that conversation would need a starting point, which brings me back to the beginning of this post. There's an argument that I should wait until I've got a little working example - I know what the first simple dynamic is I want to look at - but I'm bored of waiting for that. I just want to put something out there to taunt me with past versions of myself who'd annoy friends by trying to drag them into grand visions that I had absolutely no way of ever accomplishing. I think I might have learned how to start small and let things change as they hit reality. We'll see I guess. Hmm, just realised the Banksy quote I meant for austerity applies to me too.

Killing the idea that communal action can solve social problems

Tue, 26/01/2016 - 14:36 — danA famous Orwell quote that crossed my facebook feed:

Whether the British ruling class are wicked or merely stupid is one of the most difficult questions of our time, and at certain moments a very important question.

This 'wicked or stupid' question has been on my mind a lot recently, so it was striking to see exactly the same thought from eighty or so years back. It's the Tories I'm referring to, of course. Caveat: there are many, many decent tory voters out there - good people all. And many decent Tories in politics even. But the bunch actually doing the ruling? Well.

There are plenty of examples to choose from to characterise our current rulers, but let's start with the recent secretive push to scrap what remains of grants for the poorest university students.

If you google 'lifetime earnings university degree', the first thing that comes up is a report from 2013, funded by the Government's own Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. (Copy here if the official link goes AWOL).

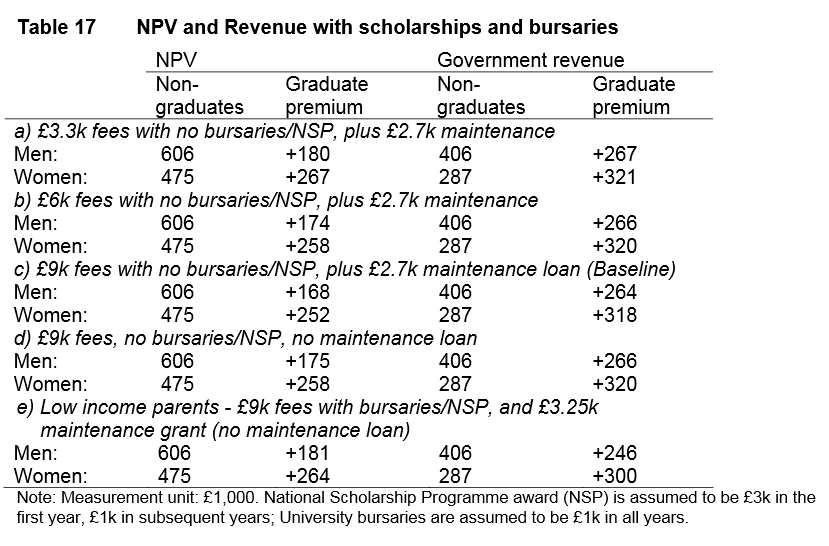

It makes clear the massive benefit of a university education for the person getting it - but also how much benefit is gained by government. I mean, the principle's obvious, right? Someone who earns more over their lifetime will pay more tax. If they end up paying more tax than it cost to educate them, there's a net benefit to the country. The word often used for this, I believe, is 'investment'. I've included the key table - this study has a breakdown by type of student, too, so we can see the gain for individual students who'd be getting the bursaries ('e', at the bottom), as well as the gain to government. The study finds a net government gain of 246 thousand from men and 300 thousand from women.

Even if those numbers were a quarter of this or less, there'd be a net gain for government. For every single student lost who decides they can't afford university any more, government coffers lose out too. Osborne claims these grants are unaffordable - that clearly makes zero sense. Ditto his point about "a basic unfairness in asking taxpayers to fund grants for people who are likely to earn a lot more than them". Taxpayers will gain, not lose out.

And that's before all the gains for the individuals themselves - in earnings and life satisfaction - as well as the increase in education levels for the country as a whole, where there's basic economics telling us the spillover gains over time for everyone.

But this is missing the point, I think - and this is why I think they're cruel, not stupid. It appears stupid only if one assumes they have the same frame of reference. They don't, not at all. No amount of logical argument on the costs and benefits will affect this government's aims. Yes, they use this language of unfairness to taxpayers, but this is little more than effective PR (which is Cameron's background, let's not forget). Flak to cover them in pursuit of the main prize.

The sell-off of housing association properties paid for by selling-off council houses shows the same aim. Housing associations are some of the last living examples of solving social problems communally. The fact that they're actually privately owned makes no difference to that.

So it's not simply a matter of shrinking the state. They actually want to kill the idea that communal action can solve social problems. A smaller state is a consequence of that belief, not a cause - which is why framing student support as an investment would make absolutely no moral or logical sense to this government. They don't see there's anything to invest in.

The NHS will go last, unless something changes. It's their biggest political goal and one that will require all of their PR know-how. They can't quite let the wolves out of the door yet - they know the political ground isn't prepared. But they're very good at this game and blithely content to use whatever bullshit argument will get them to their atomised oligarch utopia.

Hmm. That's interesting. Turns out I'm a bit cross about this.

------

New year's earnestness 3/17 , just.

How to avoid comparing rich and poor

Fri, 08/01/2016 - 18:51 — dan

Reading Mark Blaug on Pareto efficiency was a lightbulb moment. As he says, Pareto's idea was a 'watershed moment' in arguments about utility. From a distance, the outcome can seem pretty meaningless but it's an important political fork in the road - and one that shines a light on how the abstractions of economic theory get tangled with power politics. There's a story about Pareto himself to be told, too - I'm not going into that. This is about where his idea went after that.

Benthamite utilitarianism hadn't been going badly. But it was premised on the idea that different people's well-being could be compared - after all, there's no other way of knowing if you're increasing or decreasing the general welfare.

This seemed intuitively straightforward at the time. But, perhaps as the study of utility as an economic concept developed, that began to change. Attempts to actually track down a scientific measurement of people's utility got underway. Folks got upset about the obvious problems in trying to define what utility really was.

Pareto offered a way out of this. I'd known the concept before but not understood its significance until reading Blaug. Pareto efficiency: you've reached an optimal state when it's not possible to make anyone better off without making someone else worse off. Sounds innocuous enough. But notice that it sidesteps comparability. As Blaug says:

"The beauty of Pareto’s definition of a welfare maximum was precisely that it defined the optimum as one which meets with unanimous approval because it does not involve conflicting welfare changes."

It rules out the possibility that one could -

" - evaluate changes in welfare that do make some people better off but also make other people worse off" (Blaug / economic theory in retrospect/ 1997 p.573-4).

So it can say absolutely nothing about inequality. Or rather, it implicitly says that it doesn't matter: you cannot, for example, assess whether taking money from one person and giving it to someone else will improve welfare overall. Bentham schmentham.

Pareto optimality, unsurprisingly, became very popular and is essential to most general equilibrium models. I don't understand those - I'm only familiar with Krugman's spatial GE stuff, which is not the same (they're driven by explicit utility differences across space). But I'm not surprised models that, by default, exclude inter-personal comparisons should form the inner sanctum of modern economics. A model that can, by design, exclude any discussion of redistribution was always going to thrive.

Which is not to say there aren't plenty of approaches that do analyse the differences between rich and poor. But... and I'm not on solid ground with this point at all... the kind of economics that sits in rooms with ruling elites don't generally use those.

I want to make two little points about this. The first comes from having actually used utility as a concept in my modelling work and found it extremely valuable. I spent far too long listening to the siren-calls of agent modellers telling me to go towards 'realism', then in the process of slowly solving my problems, realising I had ended up back at basic micro-economics.

So first: if you're going to use utility at all, you'd better accept it's a silly idea that lets you do useful things. People are not actually utility maximisers, but the concept is a superbly effective way of thinking about how people react to cost changes in certain situations. (This is all very Friedman [pdf].)

So all that pursuit of the actual foundations of utility in our meat-brains is, somewhat, beside the point. Given that, we should use the idea in ways that are useful. Ruling out utility comparisons is just a little bit too convenient a result, politically. There isn't really any reason to, and the angst about utility's epistemological status makes about as much sense as rejecting traffic models because they don't use gravity equations. (Er, at least I think they don't...)

Second, one of the most powerful ideas that utility gives us is diminishing returns. It's easy to forget how much of a puzzle this was - the whole water/diamond problem thing. It should be blatantly obvious to anyone who thinks for a few seconds that money itself has diminishing returns. Say a 7% drop in income forces your family to eat less well and you to have to skip meals sometimes. It shouldn't be beyond our economic theory to see this as more severe than having to compromise on the Land Rover you had your eye on by buying a Mondeo.

This is kind of paragraph that sets the flying monkeys off, though. Particularly since the 2008 crash, particularly in the UK - the story that's been slowly pushed through all media channels is solidifying into political reality: such talk is the politics of envy, rather than - as it actually is - a perfectly sensible way to think about wealth.

These days I generally end up thinking "it's all about the middle way". The same applies here - effective economic comparability could imply deep intrusion in people's lives, the state charged with measuring and judging what forms of spending were more worthy than others, creating a kind of state-sanctioned Maslow hierarchy. But it doesn't need to - if one is capable of accepting the basic premise that severe poverty makes people's valuation of money much higher than for richer folk, it just implies the need for policies that reduce inequality.

And there isn't necessarily anything wrong with Pareto efficiency. The problem here is what happens when powerful abstract ideas interact with powerful political forces. Things get warped to Wizard of Oz proportions. Other perfectly sensible ideas can't get their shoe in the door. But it's foolish to use Pareto efficiency to exclude distribution thinking, just as it would be idiotic to ban its use because it was too right-wing.

I wouldn't want to live in a world where political schools had their own paid-for economic theorists. I do still believe in the pursuit of actual social-scientific truths. But Pareto efficiency is one of those ideas that hammers home just how hard it is to pull economics and politics apart.

The point: as far as possible, your economic/mathematical models shouldn't rule out one particular political way of thinking. The choice of how we balance wealth in society - that's a political issue. There's no easy way to keep an unbreachable line between positive and normative - modelling methods will always interact with our political assumptions and power structures in sometimes very-hard-to-see ways. And I also believe in the power of quant modelling to help us understand which things may not work if pursuing certain political aims. But modelling distribution issues - and using utility to do this - no more makes you a communist than using Pareto efficiency makes you a fascist.

(p.s. googling Pareto inequality reminds me there's a mountain of stuff on this subject I don't know. But if I think like that all the time, I won't get a single blog entry written, let alone seventeen...!)

------

New year's earnestness 1/17

Would you trust Uber and Google with your city streets?

Mon, 15/06/2015 - 20:09 — danUber-branded taxis are now ubiquitous* in Leeds, having launched last November. I'm back in Leeds for a month - it was immediately striking that pretty much every taxi now has the large white Uber label, at least in the city centre. That's a pretty impressive transformation in just over six months.

It's a classic disruptive firm; one can imagine CEO Travis Kalanick has personal targets for how many local government authorities to annoy. It can certainly be spun as a nimble tech firm zipping around the tree-trunk legs of a geriatric industry. Predictably, there's been trouble. As well as various protests, some Uber drivers are getting organised to fight for a bigger slice of the profits. (If, as that article says, Uber are taking 20-25% per ride, there isn't a lot of head-room for wages to increase - Uber's dirt cheap fares would have to rise.)

Uber have placed themselves between drivers and customers in a way that reminds me of the weirdness of Apple's app store. In a world where anyone can dump code on their blog and anyone can downoad it, Apple have thrived by creating a portal and sitting as gatekeeper. They take around 30% of every single app sale - and, for developers, this has actually worked out great. They get access to a huge market while getting to code on a single, predictable platform. Small niggles about the political implications of that control might buzz about irritatingly but cause no serious discomfort.

Equally, existing tech could - in theory - link customers and taxi drivers without the need for such a powerful intermediary. The possibility of open-standards platforms transitioning us to the next level of transport has excited many people. Harvey Miller's work, for instance (and this great presentation) sees hope for a "transportation polyculture" where smart-city tech opens up a world of collaborative/co-operative transport. In this world, the kind of fluid, efficient city roads that Uber talk about, where ride-sharing is easy and prevalent, come about via open source principles entirely at odds with Uber's - though such a world would perhaps be just as disruptive to existing taxi firms.

Two radically different internet myths are at the heart of this difference. In one founding myth (as the Economist says) the Net is "the spontaneous result of co-operation by growing numbers of people acting outside the control of the governments and big companies" - a "libertarian paradise" promising a level of openness, connectedness and democracy never before possible. That story is still being told.

But then this other story appears.

Blood, sweat and containerisation

Wed, 19/05/2010 - 10:08 — danThe last episode of blood, sweat and luxuries aired on BBC3 last night. In this series, a bunch of UK consumers have been made to work on products that end up on British shelves. They stay with other workers for the duration. I've only caught two of them, but it was powerful stuff, if occasionally cringeworthy watching some of the Brits deal with it. A 'part time male model' in particular seemed to wear his outrage in front of the camera as an accessory, and mostly flounced off the jobs after an hour or so.

Last night's saw them working in a relatively small Phillipino components factory in Manila - called EMS - making small changes to a hard-drive wire for mp3 players in a cleanroom, looking out through a tiny slit in their blemish-free gowns. The factory is in Laguna, the 'Silicon Valley of the Philippines.' (Google found that in a copy of the Philippine Daily Inquirer from 2000. How did it do that??)

To begin with, they clown about; when the supervisor points out the workers are trained not to look up from their work regardless of what they hear, a couple of them take to banging on the windows - and indeed, no worker moves from their task. "Every unit takes 3 seconds, a single glance takes 3 seconds," points out the supervisor, "so you will fail to meet your output."

Meat and symbols

Sat, 27/03/2010 - 10:20 — danOften, in the moments between sleeping and waking, ideas become visceral, almost literally. This can include things like 'oh my God, Sarah Palin might be one heartbeat away from leader of the free world' or 'oh my Christ, we really are managing the fuck the one planet we have.' That last one is often accompanied by the 93 million miles between the Earth and sun shrinking so that the heavenly bodies are almost within mental grasp, almost in the same room. There really is a star blasting at us, churning our water and atmosphere.

More recently, there's been a few occasions when it's been more corporeal: yanked back from sleep and plopped into a vast dark room of consciousness, so I can have some stark fact about my physical form klaxoned at me. For some reason, my spine got that treatment (probably because of a bad back); a keen sense of bone and gristle holding my centre line together. More recently (probably after some film or other) my brain decided to get all 'aaargh' at the idea of a bullet going through it. Quite reasonable thing for it to do, one might think. The fact that usually it doesn't says something about our ability to just get on with what the world presents us with. But right then, my brain wasn't having any of it: so, here's a bullet, right? It goes through and me, this person - suddenly I'm goo, I'm all over the place.

One hundred years

Thu, 11/03/2010 - 11:15 — danI went to hear Nicholas Stern speak a couple of nights ago: the subject was 'after Copenhagen'. It was a great talk; the man has the gift of speaking in a way that, written down, would make excellent reading. (A skill many politicians learn early.) But I was struck most forcefully again by timescales we now now talk about: what will happen in a hundred years? Current emission rates, according to climateinteractive, give a mean of 3.9 degrees. (OK, that's 90 years...) The spread's wide: if we're lucky, closer to 3, if we're unlucky, closer to 5. It hasn't been 5 degrees above current temperatures for 55 million years. Stern had a nice turn of phrase: these are the kind of changes that move people, move deserts, and are already manifesting as season creep (discussed in this recent paper that attempts a robust framework for analysing the impacts. No model in sight there: 30 years of data.)

One hundred years. Very few humans last that long. A hundred years ago, no first world war. The Los Angeles International Air Meet showcases some crazy new designs. The first commercial air-freight flight takes place - and the first commercial dirigible flight. (Now, this many flights happen in a 24 hour period.) Albania rises up against the Ottoman empire. George V becomes king. Wow - the Vatican makes all its priests take a compulsory oath against modernism. Mark Twain dies; 1.75 billion people live on.

It turns out the past is a different planet. Let's make a prediction: a hundred years hence, it'll be a different planet again.

Climate science and the political compass

Wed, 04/11/2009 - 10:18 — danIn all my banging on about good science yesterday, I realise on one thing I was being unscientific. A couple of links, to Next Left and Crooked Timber, wondered why there seemed to be such an anti-AGW consensus on the right. I speculated it may have something to do with a different assessment of the risks - but this is missing a basic question that could be asked. I'll ask it now, and then suggest that it doesn't matter anyway.

Recent comments

21 weeks 6 days ago

2 years 12 weeks ago

2 years 12 weeks ago

2 years 14 weeks ago

2 years 15 weeks ago

2 years 15 weeks ago

3 years 12 weeks ago

3 years 36 weeks ago

3 years 36 weeks ago

3 years 38 weeks ago