Blogs

Economics: reform or revolution?

Fri, 05/01/2018 - 18:41 — danDigging into economic arguments around austerity has been like accidentally walking in on a pub brawl: honky-tonk piano still playing, people being hit with chairs, others thrown the full length of the bar breaking all the glasses, someone thrown through the first floor balcony etc. Nobody gets this worked up about spatial economics.

I've been doing this digging since this little fantasy post about the idea of making austerity economics more visible (or, rather, making macroeconomics more visible, and so arguments about austerity more transparent). It's been a dream for a long while, probably since first discovering the MONIAC machine, the (currently not working) prototype of which sits in Leeds University's Business School foyer.

I've taken a few baby steps in that direction1 - it may never come to anything, but the process of attempting it has churned up a whole load of economics stuff I haven't thought about in a long time.

I've found myself flummoxed by some of the things I'm seeing in the bar brawl. Exhibit A: Steve Keen's cartoon - taking the CON out of eCONomics! - from which we learn, apparently, that Krugman and Summers "don't know what they're talking about". Blam! Thwack! Keen's mode of operation may be extreme in heterodox circles but it seems to be wildly popular.

I've also just got a copy of James Kwak's 'Economism': so far, this has been a much more measured book with very little I disagree with. It acknowledges the power of economic thinking - but it paints a convincing picture of "economics 101 as ideology", captured and promoted by particular elites, turned into a propaganda tool. On my first skim, it doesn't recommend smashing everything to bits, but instead changing institutions, expanding and re-weighting curricula.

As it points out, the emergence of 'economism' can be seen just in how topics were re-ordered over time in Samuelson's textbook. It quotes a THES article...

"Economics degrees are highly mathematical, adopt a single narrow perspective and put little emphasis on historical context, critical thinking or real-world applications."2

...but notes that, once one gets past this highly standardised economics (largely harmonised with ideological economism), actually, there is a great deal of much more subtle economic thinking going on. It's just that students aren't initially exposed to it.

I don't know how true that is - I suspect economism of the sort pushed by Paul Ryan when he's showing woefully simplistic supply/demand curves to justify dismantling Obamacare (an example from the book) has a messier relationship to taught econ101. But the book's central claim - that there is a version of economics used as an ideological battering ram - is hard to argue with.

Self-indulgent background follows for several paragraphs... I'm in an odd, sort of lucky, sort of rubbish, situation: for the PhD model (finished 5 years ago now, oi...) I found some economic ideas incredibly useful. While I'm still pretty insecure on my views about this (it was just me in a dark room building a model for years and those ideas remain largely untested) I perhaps got a unique perspective, being forced through trial and error into finding how useful economic ideas can be, rather than having to learn and regurgitate the orthodox package.

I got to jump off the rails and go wandering freely. The model itself forced me to think critically and historically - I ended up running about randomly on the economic landscape, solely on the look-out for ideas that could move the model forward.

There were no stakes (besides me finishing the ****ing thing): I just found micro-economics really useful for modelling how people and firms react to cost changes if they're embedded in space, and that agent modellers' claims to better "realism" made no sense in isolation.

When it comes to austerity and macro-economics, obviously the stakes get a lot heavier - and much more ideological. Black-hole gravity wells of ideology can warp even the purest scientific disciplines so it's unsurprising what a mess it makes of economics.

Before the PhD, I started off with the same worldview as many heterodox economists. I'd studied politics at Sheffield and fully took on board the standard, incredulous dismissal of homo economicus, the perfectly rational calculating machine: insultingly reductionist, logically absurd (Friedman's "realism of assumptions don't matter" line, a caricature of his actual argument, would exemplify that idea) and nothing more than a figleaf covering the goolies of power.

I found the strongest confirmation of this in World Bank reports studied in my final year. One of them claimed the goal in developing countries should be to "supplant or amend" (change or die!) all "behavioural norms" that were "market dysfunctional" and replace them with the market-functional versions. It contained an entire "tactical sequencing" plan (divide and conquer!) to overcome state and societal resistance to this supplant/amend plan.

It looked for all the world like a strategy for creating homo economicus, for transforming entire states to achieve this. It's easy to assume reports like this reflect the Sauron-like power of neoliberalism, rather than just whatever the writer happened to think that day (as well as being just confirmation bias). But it does support the 'Economism' idea: global market norms are pushed by powerful organisations. And economics is the theoretical branch of that push.

On the academic side, you can also see how methods become shibboleths. As Krugman says, his geography ideas needed to be expressed as a general equilibrium model to be accepted:

"Mainstream economics isn’t going away: like it or not, the White House has a Council of Economic Advisers, not a Council of Geographical Advisers, the World Bank hires lots of economists and not many geographers."

The World Bank and other organisations have worked to recreate this same structure, including setting up and staffing finance ministries around the globe. (Says 2002 me - 2018 me replies, "well, did that happen and how successful was it?" I don't know. I do know trying to implement such plans always tangles with messy reality in unexpected ways. And that the World Bank has radically changed since then...?)

So while I kept to my little dark room, building spatial economic models, I found basic economic modelling ideas really really useful. But beyond that, in the bar brawl of macroeconomics, things get a lot messier - there really is global power, propaganda, economism to contend with.

Being simplistic, I can imagine two heterodox ways to think about that reality: revolutionaries and reformers. Where Keen might be a revolutionary, Kwak is more of a reformer (he's clear about that in this blog post). The revolutionaries won't be happy until the Great Neoclassical Tower of Barad-dur has come crashing down, having thrown the... err... Ring of Microeconomics? Into the lava of Mount Marginal?

That's not a political mapping: these revolutionaries are not necessarily more leftie. It's just that they want to throw the theoretical baby out with the ideological bathwater. I get the sense my idealistic notion of creating a clearing for transparent discussion of macro method just wouldn't work for some of those folks. (There may be some also who object to quant modelling generally - I'm saving that for another post.)

And the fact that it's wildly popular does worry me. I wonder if these attacks aren't playing the same ideological game, just as awash with shibboleths as their target. It doesn't seem like a way forward to me, if we really want to develop methods and institutions that can actually manage national economies well, or even - crazy idea I know - maintain a functioning biosphere.

Whether the actual visualisations ever happen - definitely still in the realm of fantasy but I am trying little baby steps! - there's a lot else to think about here. Stuff about realism in particular, about how different methods should be valued or discarded, seems essential to me. I still haven't really clearly explained why.

Also, more careful thought needed on how this all connects to economism. I keep on defending that one chapter by Friedman because I found it really useful at a critical moment - yet he's also a central figure in the creation of economism as an ideology, it seems. Can these two halves in my brain be reconciled?

But the fantasy idea is still appealing: arguing the case about the actual economic method in as transparent a way as possible, using visualisation, models with methods all arguable and clear via github, without diminishing the importance of the political economy. Dream on...

-

I've also been upping the necessary tech skills - it turned out jumping straight into an online macroeconomics sim was bit much so I'm practicing on house prices; unfinished prototype is going well - those numbers are wage multiples, slider is 1997 to 2016. ↩

-

James Kwak, Economism, p.188 ↩

How to make completely opposing claims using the same survey data (or: how to cherry-pick)

Thu, 23/11/2017 - 15:53 — dan

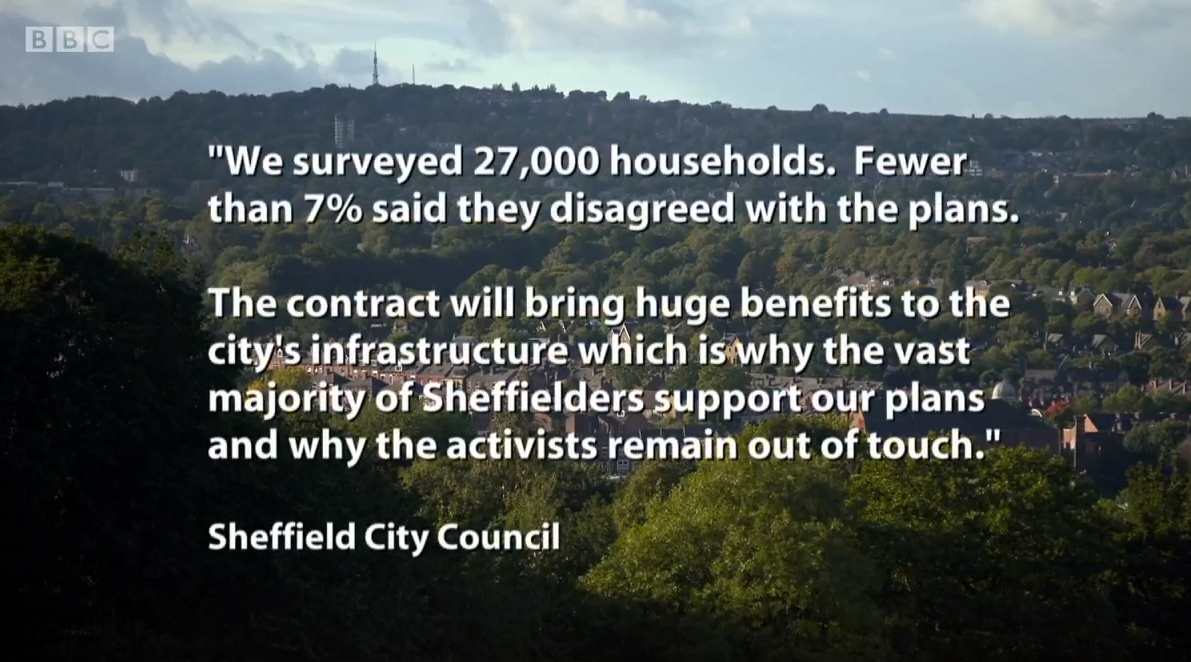

Sheffield Council put out a statement on the BBC recently, during an episode of Countryfile, defending their outsourced Streets Ahead contract against accusations of needlessly felling thousands of mature street trees:

We surveyed 27,000 households. Fewer than 7% said they disagreed with the plans. The contract will bring huge benefits to the city's infrastructure which is why the vast majority of Sheffielders support our plans and why the activists remain out of touch.

Only a small minority ('fewer than 7%') oppose their plans? And 'the vast majority of Sheffielders' are in support? Here's the thing. Using exactly the same data Sheffield Council have used, I could put out the following equally correct statement, in support of the tree protestors:

Fewer than 7% of households said they agreed with Sheffield Council's plans. The vast majority of Sheffielders oppose their plans. The Council remains out of touch.

Wait, what? Only a small minority support the plans? That's entirely the opposite message. How can the same numbers support both of them?

Well, you have to do two misleading things. First, you need to cherry-pick a number. Second, you use a dubious statistical choice that makes it look like a tiny minority oppose the plans, when in reality the data shows an even split of opinion.

Let's go through those two. First, the cherry-pick. The actual survey numbers are as follows. The total number of households they posted letters to is 26677 (round up and you get '27000 households'). 3574 households actually responded - that's 13.4% of total survey invites. Of those 3574, 1774 households opposed the plans and 1800 households supported them.

1774 opposed, 1800 in support? That sounds like something close to an even split of opinion - and indeed, it's not statistically distinguishable from half against, half in support. Not a tiny minority, not a vast majority.

If we cherry-pick just one of those and ignore the other, we're half way to making one of our two opposing statements. The next step: ignore that you should use the number of responses to your survey (3574) to work out the percentages and use the number of letters you posted instead (26677).

By doing that, you can get the 'fewer than 7%' number for both. So we can cherry-pick too: 1800 in support as a proportion of all the letters posted? Fewer than 7%. (1800 over 26677 then multiplied by a hundred to get the percent.)

If exactly the same numbers can be used to produce two completely opposed statements, I hope it's obvious that you're doing something wrong and the numbers are being misused.

The council have defended the statement saying it's factually correct. If you squint, you can just about see how 'we surveyed 27,000 households, fewer than 7% said they disagreed with the plans' is technically true. But I've just shown how the same 'technically true' method can be used to support entirely the opposite message. That's the power of cherry-picking.

And it's not a one-off either. Via the Streets Ahead twitter account, the same data was used to claim only a tiny minority on one street opposed the plans there:

Our household survey results show that of the 54 households on the road, 5% opposed our proposals for street tree replacement.

You won't be surprised to learn: there were only six actual responses on that street, 3 for and 3 against. So again, it's equally correct (but still inappropriate) to say "5% supported our proposals". (It was Rivelin Valley Road, so's you know - again, the numbers are in the document above.)

All of this is ignoring the 'vast majority of Sheffielders in support' statement. In a way, this is the most worrying part. It's just plain wrong, if we're going by this data. But in the context of the 'fewer than 7%' line, I can imagine how one might think, 'well, more than 93% must be in support then'. That's kind of implied, isn't it?

Yet as we've just seen, using the Council's (inappropriate) method, it would actually be 'fewer than 7%' opposed and 'fewer than 7%' in support. They not only omitted to mention this, they have added in a 'vast majority' claim that appears to be completely unfounded. So we're clear, there's nothing in these numbers that even remotely supports a 'vast majority' either for or against. It's an even split.

The ethics of numbers

If your idea of factually correct allows you to make entirely opposed claims with the same numbers, it means you are likely cherry-picking: "pointing to individual cases or data that seem to confirm a particular position, while ignoring a significant portion of related cases or data that may contradict that position". Though here, the cherry-pick wouldn't really work without also mangling how surveys are meant to be used.

I work with numbers in my job: it's a matter of professional ethics to make sure, as much as we can, that our work can be trusted. (Have a read of this code of practice from the UK Statistics Authority - it's a good take on the kind of integrity and honesty we're supposed to aim for.)

We don't know how Sheffield Council created this statement. I can imagine a single over-worked officer under great pressure to get a message out at short notice. But I don't think it's unreasonable to expect the same level of trust from our local councils when they use statistics.

As Ralf Little recently said to Jeremy Hunt (I paraphrase slightly): 'the good news is, now that you know that this statistic is total nonsense, you won’t feel the need to use it again'.

The actual numbers

Let's end on looking at what this survey actually does show - that there's a pretty even split for and against. I should start by saying, we shouldn't really be using the independent tree panel survey1 for this at all. Households were asked their views on trees on their own road. They were not asked, 'do you support or oppose the city-wide Streets Ahead plan for tree management?' They also surveyed households, not individuals. But I guess that's small potatoes compared to the above.

27000 households (rounded up) is the invite number and 3754 is the response number. Trying to maximise response number is central to any survey: the higher the response rate, the more your sample can be relied on to accurately capture what the larger group thinks.

This is hopefully obvious, but let's spell it out to be sure. We don't know what the households who didn't respond think. This is the entire point of surveys: get a sample of views so you can make deductions about everyone else.

So here, the actual split in the response numbers I gave above is 49.6% opposed, 50.4% in support. I may get round to another post explaining why this can't be statistically distinguished from an even 50/50 split - though the intuitive idea is just: how much could that split change as you get more responses? Here, we have a 16% sample - that's pretty big. It's very unlikely to change a lot, but because it's so close to 50%, it could likely shift either side of that 50/50 mark.

At any rate, it is astronomically unlikely that 'fewer than 7%' is the correct percent opposed. For that to be true, all the other households that didn't respond would have to be 100% in favour. The 16% sample would have had to have picked up on every single household opposed. Just... no.

So to end: whether or not the Council knew they were doing this, they have selected numbers to support their own message - as I've shown with a statement claiming exactly the opposite, using exactly the same data and method. This is some way before worrying about sampling rates and confidence intervals. And the 'vast majority' thing... whu?? So let's just end with a tip:

- Check if you can put out two equally true but mutually exclusive statements using your method. If you can, your method is wrong. Try again.

-

Sheffield Council surveyed households, one street at a time, to find out if residents wanted an independent tree panel to re-examine decisions about trees on their street. Again, the data is here. It collated all of those single street surveys into one document. ↩

Can a Tralfamadorian make predictions?

Tue, 31/10/2017 - 07:56 — dan

Tralfamadorians are four-dimensional alien beings able to travel anywhere in time as well as space. Or so Kurt Vonnegut reports, quoting one as saying:

"I am a Tralfamadorian, seeing all time as you might see a stretch of the Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is. Take it moment by moment, and you will find that we are all bugs in amber."

My question for the day: could a Tralfamadorian make predictions? Short answer: yup, totally. Longer answer -->

Our root for the word 'prediction' wouldn't make sense to a native of Tralfamadore. It literally means pre-show - to "say or estimate that (a specified thing) will happen in the future".

This has always seemed a bit odd to me, only half of how we actually use the term. Looking at things from a Tralfamadorian perspective makes this more obvious: the word 'forecast' has no meaning on Tralfamadore. All past and future events are accessible to them. There's no such thing as a Tralfamadorian weather forecast. They don't bet on horse races. They can't try and game the stock market. They can't actually have a stock market.

But they could still make the kind of predictions we consider among the most important: what Gregor Betz calls an `ontological prediction'.*

Here are three famous ontological predictions (one mentioned by Betz). One: the existence of Neptune deduced from oddities in the orbit of Uranus (I see you snickering...). There was either another planet or Newton was wrong. It turned out there was another planet. Then two of Einstein's: light should appear to bend as it passes through gravity-warped space; and the existence of gravity waves. The first was famously (though not uncontroversially; see also this) confirmed by Eddington during an eclipse.** Confirmation of gravity waves is brand spanking new. Immediately, they are cosmically awesome, able to dig deep into the universe to solve the riddle of where some of the heaviest elements like gold come from (neutron stars colliding... whoooaaa).

So - those were all predictions, yes? And each did provide statements on the future - but only kind of by default. The future is the only place we can test our theories. On Tralfamadore, that's not true. Tralfamodorian Einstein could come up with his theories, look up a suitable eclipse in the seventeeth century on his four-dimensional road map, pop over to meet Newton for a bit of co-corroboration, maybe nipping to Papua new Guinea in 1698. (Probably best not to over-think it... wouldn't all Tralfamadorian predictions instantly propagate everywhere/when? So everything would by necessity be known instantly leaving nothing to be discov... oh, they're just a fictional device for making a point, OK then. Phew.)

All of which is a slightly belaboured way of saying: ontological predictions are fundamentally different to forecasts. They are timeless (though the realities they seek don't need to have always existed). They are about seeing things that were already there but we didn't know to look for.

The fact we have to test our ontological predictions in the future doesn't change how different this is to a forecast. It's unfortunate our definitions reinforce the idea that `predict' and `forecast' are the same. Of course, the two are dependent on each other: actual forecasts need underlying theory, and discovering that theory is an ontological-prediction job. But there is conceptual clear blue water between the two of them. New forecasts using an existing method don't require extra ontological prediction. You could also, for instance, improve weather forecasting independently of ontological prediction by throwing more powerful computation at it or some novel refactoring, without making any deeper discoveries about the underlying physics.

Why does this matter? Well, this is all a pre-amble to another post: after reading another attack on a cartoon version of Milton Friedman's argument about model assumptions, I feel like having a proper go at exploring why those (seemingly very popular) arguments miss the point, and why that's important. tl;dr: he never said "assumptions are irrelevant". He did say predictions are the ultimate arbiter - but it's hard to get very far without being clear what prediction actually is.

Once you start digging into this, it also ends up saying something about how different disciplines see themselves, how the public sees them, and how we frame the entire research enterprise in applied versus non-applied terms.

It's also a trope used by many people to reassure themselves that the entire edifice of economics is clearly stupid. That's annoying, wrong and that used to be me. But it's also used by people who should know better to bolster their economics-heretic credentials, and that's especially annoying. So, more at some point before 2019, I hope, or possibly before now if I can find a Tralfamadorian to work with. Thoughts gratefully received in the meantime: does this two-part distinction in prediction scan?

Update: oh, it turns out Friedman was quite explicit about including ontological prediction in his definition: "to avoid confusion, it should perhaps be noted explicitly that the "predictions" by which the validity of a hypothesis is tested need not be about phenomena that have not yet occurred, that is, need not be forecasts of future events; they may be about phenomena that have occurred but observations on which have not yet been made or are not known to the person making the prediction. For example, a hypothesis may imply that such and such must have happened in 1906, given some other known circumstances. If a search of the records reveals that such and such did happen, the prediction is confirmed; if it reveals that such and such did not happen, the prediction is contradicted." Source.

--

* Note Betz also thinks a prediction is a "statement on the future".

** Skipping over gravity having Newtonian effects on light - look, a black hole prediction!) Though if I'm reading that right, it's based on light being a particle with mass.

Don't cling to a mistake just because you have spent a lot of time making it

Sun, 30/07/2017 - 21:13 — dan"The chances of the government admitting that austerity has been a failure are precisely zero. That would mean telling voters that all the sacrifices since 2010 had been in vain." (Larry Elliott)

"Don't cling to a mistake just because you have spent a lot of time making it." (Banksy)

There's a school of thought that says ideas are like Soufflés - if you don't give them just the right care when you're baking them, letting the scaffold form as it should, they collapse in a gooey mess. I used to bake a lot of this kind of thing. I didn't get better, I just stopped trying - too ashamed of all the sad little sticky puddings. But I figure I'm a bit older and, if not wiser, more cautious now. Just throw some stuff out there, poke things a bit and see what happens. Do the thing and all that. Nothing may come of any of it, but then nothing will come of nothing if nothing's all that's done. Profound. So that said...

I've got this notion that it should be possible to show how the economy works in a way that's both robust and accessible. I don't mean accessible just from a three minute glance, infographics-style. But it should be possible - for example - to drag otherwise murky arguments about austerity out into the light where you can test views based on what's actually known, obvious, possible. You'd aim for reducing the range of ambiguity to something much less overwhelming. Expanding the little pool of clarity into something much more vivid.

The reason this draws me in is pretty simple: the 'sacrifices' Larry Elliott talks about - they're almost impossible to grasp. The things that have happened, are happening right now, to people, institutions, all apparently to right a listing economy - there seems to be a very strong case this was all totally unnecessary, literally counter-productive and utterly wrong-headed. And the arguments aren't all that abstruse - it shouldn't be that hard to mark out their boundaries. (Hah - note that for later.)

I'm not naïvely imagining there's some process of alchemy that can transform how the austerity debate is seen (or macro more generally). There's a whole bunch of people that are obviously inaccessible to what I'm talking about, not least those ideologically opposed to the idea of any state action who've seen the crisis as an opportunity. They'll continue to push whatever sophistry furthers that aim, of course. There are also people on both sides who Just Know and nothing could possibly convince them otherwise. (I like to pretend I'm not one of those, though don't we all?) Others won't have anything to do with quant of any kind, especially economics-plus-quant: for them, it's an elite-wielded tool propping up power. That's one to come back to - I have some sympathy for this but it's confusing the tool and the user.

That leaves a whole swathe of people who can meet and converse, given the right space and tools. Have no truck with the convenient lie about post-truth. The global response to Trump pulling out of the Paris Accord shows it's the idea of post-truth that's the danger - something well understood by regimes like Russia. (Paul Mason nails this brilliantly in his stage take on 'why it's kicking off everywhere'.)

I'm not saying there are always right or wrong economic answers, but you should be able to set out what the spread of rightywrongyness looks like. And if I'm talking about a tool, this would mean transparency in how it's built too. Code would need to be accessible, assumptions up-front, well commented and explained. The way models are perceived (even by many modellers) leaves a lot to be desired - I'd see this kind of open process as a chance to talk about that as well. It couldn't be something you went away for years to build - the building process itself would need to be a conversation. It couldn't be - initially at least - some single overarching model (h/t Jon Minton).

But that conversation would need a starting point, which brings me back to the beginning of this post. There's an argument that I should wait until I've got a little working example - I know what the first simple dynamic is I want to look at - but I'm bored of waiting for that. I just want to put something out there to taunt me with past versions of myself who'd annoy friends by trying to drag them into grand visions that I had absolutely no way of ever accomplishing. I think I might have learned how to start small and let things change as they hit reality. We'll see I guess. Hmm, just realised the Banksy quote I meant for austerity applies to me too.

Tasered by Trump, plus some vague thoughts on melting ideologies

Tue, 06/06/2017 - 17:27 — danMaybe Donald is exactly what the Earth's biosphere needs. As Robert Orr put it, regarding his pointless Paris tantrum (the agreement's entirely voluntary Donald - exactly what costs were being imposed?):

The electric jolt of the last 48 hours is accelerating this process that was already underway. It's not just the volume of actors that is increasing, it's that they are starting to coordinate in a much more integral way.

People who might previously have been thinking, 'aah, the government's probably got this covered' are realising - not so much. They've been tasered by Trump. And that integral coordination he mentions - that's a marvelous, essential thing. If Elinor Ostrom was right, it's also the only thing that will work. (Oh look, an entire paper of hers on climate polycentrism.)

It'll be intriguing to watch what happens in the US as that coordination ramps up and builds links with the rest of the planet: a different model of the voluntarism already built into the agreement might form something a lot more Ostromy. I feel a lot more hopeful about that than anything involving global agreements that include techno-pixies like BECCS. (If a polycentric world actually demonstrates something that works, that's another matter, but let's not rely on non-existent things, huh?)

Which is not to say that large-scale, often government-supported, things aren't necessary - we're not going to be short of those though. But anything that's an electric jolt out of someone-else's-problem-itis has to be a good thing. (A little thing got done here, even, that I managed to find a way to contribute to, after the actual US-election jolt. More on that some other time.)

One of the main things I'm mulling at the moment goes back to all that political compass stuff. No, it's more than that - it's about how we break out of assumptions that keep us cemented to the spot, when we need to be learning to move. Hmm - not explaining this well.

David Mitchell's take on climate change is actually a pretty good way into talking about this. He does it in a slightly more sarcastic way than is perhaps ideal, but still... And take this first sentence with a pinch of hey-its-comedy-so-its-OK:

It seems such a pity that the clear fact of climate change is seldom expressed by people who don't seem just a little bit pleased by it. Similarly, sorting it out is always presented as an opportunity or a pleasure or as something we ought to have been doing for years anyway. In fact, it's just a thing - a really depressing thing that's happening, but the people who tell us so always seem to be radiating one or both of those old parental stand-bys: I warned you this would happen - or, hey! Clearing up can be fun!

There are also often slight undertones of disparagement about industrial pioneers and the human urge to innovate in general. As if poor old George Stephenson should have known perfectly well that when he got that kettle to travel along rails it would lead inexorably to planetary jeapardy. Well, take that to its logical conclusion and you're labelling the first caveman who ever fashioned an axe as a cross between Dr. Oppenheimer and BP.

There's a whole load of other quotable stuff in there (the point about Clarkson driving to the North Pole in a 4x4 drinking G&T being obviously more fun than sorting out the climate, for example...)

I can only just start writing about this now, but let me just note for myself what I want to come back to. If climate change straightforwardly slots into your existing political worldview, you're not questioning that worldview enough and you're probably alienating a bunch of people in the process. The Age of Stupid do that here, for example. Naomi Klein's obviously done it: oh look, climate change proves I was right all along about the need to overthrow capitalism.

I'm, not quite, saying this is all wrong. That's not my point. I think I probably want to have a go at any ism at all, any totalising way of thinking. Which may be a problematic argument given that we seem to run on stories as a species, and stories generally need some coherence to them for us to not slip into a ditch of horrific depression.

Let me just put this here as a working hypothesis - something I want to think about and may well end up completely reversing my position on: I suspect there are very, very few political worldviews that couldn't survive in a climate-constrained world in some form not too distant from its ancestors. (Most ideologies are flexible enough to survive new circumstances.) Which means, logically, it's also possible to have the same arguments we've always had about those. To the extent that climate change becomes umbilically linked to the victory of one particular worldview, that stuffs any real chance of genuine dialogue to solve it.

At the same time, that doesn't minimise the profundity of the situation we're in. I'm some way through Clive Hamilton's Defiant Earth - as well as being one of those rare writers with the ability to be crystal clear, it's also a fantastic deep dig into the anthropocene with subtle, mercurial thinking. We need more of that and less 'climate change confirms that my existing worldview must conquer all or we fry.'

I think, maybe. Err. More mulling needed. Lack of conclusion or perfection no reason not to post on blog!

Great recession caused the dirty oil boom? (plus bonus self-indulgent whinge about writer's block)

Fri, 02/06/2017 - 11:52 — danHere's something (PDF) I didn't know: monetary easing (QE and near-zero or even real-terms-less-than-zero interest rates) might have been responsible for the dirty oil boom and the subsequent price drop. (That's via a little summary of Helen Thompson's book).

It does also make the 'recessions always correlate to oil price hikes' claim you'll see being made by people I might call oil determinists. As she does here, even the recent mortgage credit related crash looks like an oil-triggered thing through this lens. Others, however, see e.g. the 70s oil crisis being made much worse by governments whacking the steering wheel in the wrong direction in reponse to what happened.

But this story about how massively expensive dirty fuel exploitation got going makes sense - and fits with the kind of up-down pattern we can probably expect without anything to counter it. Though I'm trying to picture how that ends and can't - if, for example, renewables continue to undercut fossil fuels, demand for them drops, their price drops... and what's the new equilibrium? How do you eventually see the end of an old energy source, as we have several times before?

Dunno. But I'm going to post this anyway, and try and post anything else interesting I find, as all I've been doing recently is writing abortive chunks of whinge about how I can't write any more. The first thing I need to do to fix that is (a) post little things like this even when this new 'you don't know enough about this' warning light I seem to now have courtesy of academia starts blinking in the cockpit and (b) even when I write horrific sentences like this, still post it because that's better than filling folders full of words that never get posted (well, maybe not for anyone reading...) and (c) work up slowly to the larger topics I keep on trying and failing to find a way to articulate.

I do want to write about what's happened to the writing (and thinking etc) because there's something important there. But it needs working up to and I'd feel better about doing it if I've got the wheel going a little under its own inertia.

The short of it seems to be: I used to love writing but I'm not sure a love of writing can survive in academia. No, correction: not sure my love of writing can. If there was some way for me to find a happy marriage of my own needs and what's required of me... but there, starting to whinge about it, I'll save that for later.

Let's see if it's another year to the next post.

Letter mainly to myself, post-Donald

Thu, 17/11/2016 - 08:49 — danI think I've probably finished the reading the internet now. Eyelids peeled back, unable to look away, scratching the wallpaper off to get at whatever thoughts or feelings might help shift this... matter through my digestive tract without rupturing something. It's ongoing. In the meantime, as for so many others, dream and reality are in some godawful state of twizzler. Panicked braincells scramble to hide behind each other, desperately straining to avoid the incoming signals.

Which is of course all angel delight to the right-wing maw. As a friend once said after they inflicted a vicious chess defeat that I'd poured everything into: "I wear your pain like a crown."

Well fuck them, obviously. (Not the friend - they're quite nice really.) Paul Ryan's vacant little Mona Lisa smile as he refuses to acknowledge that an appointed 'chief strategist' is clearly Voldemort - that's pretty much all we need to know about these people. "Evil overlord, you say? Hmm. Will this get me more power? Mmmmm."

I've been shocked into doing something. Pretty messed up that it should take this, but there's some comfort knowing exactly the same thing must be happening to thousands, millions of others.

There are a bunch of luxuries we no longer have. We don't have the luxury of much self-doubt. Or rather, it'll always be there - everyone has it - but you're not allowed to let it stop you. Them's the rules now. Do something. Anything from contacting people you haven't in a while, hugging a friend, donating, volunteering, painting, singing, plotting, inventing an entire utopia. Don't make a utopia in your spare room all alone though, and don't be silly and try and do it all on the internet. Come out and play. Bounce that stuff off other people - the one thing we need more now than ever is to connect with others in every way we can.

Sure, your mind may scowl: "you Walter Mitty peabrain, what the hell makes you think you can make any difference to anything? Remember all those things you fucked up? That's the real you. Drink your effing beer, stuff this Netflix into your eyeballs and SHUT UP." But... your mind can fuck off as well. And notice just how useful that bit of your mind is to those aforementioned power-mad eejuts. They want you to do nothing. Fuck them also. I said that already.

Because there are really very sound reasons why you should do the thing and not not do the thing. Jane Jacobs nailed it: anything good that ever happens or gets made is just accident fuelled by intention. It's a lot of people with ideas and bits of stuff they're making and trying, doing the thing - and usually finding out the thing doesn't turn out anything like how they thought. But then this other thing happens - Jacobs realised, in fact, that it happens without fail when we get together to do stuff. It's what humans do. Some magic mix of evolution and artistry: person A goes - hey, that thing you just did? What if I just bodge that in with this other thing? Oh sweet Christ, we've discovered a better way to organise the city! How did that happen?? Accident fuelled by intention, ladies and gentlemen.

But it needs the intention. You need to turn up, do the thing and - this bit is especially important - not not do the thing. Not doing the thing: that's self-doubt's job description. Spotting little green shoots of maybe doing the thing and yanking them up before you have a chance to get out the door.

And you do at least sometimes need to get out the door: do the thing where other people are doing things too, or take the thing out for a visit now and then.

So - for myself - I'm fucked if I'm gonna let some colossal tango-faced bullshit queen, centre of a venn diagram made from a blow-up sex doll and an obese geriatric ginger tomcat, mess with everyone else's amazing work on stabilising carbon output. It should probably have been obvious this couldn't be done without one or two countries going the full man-toddler on us. A puncture on the road is predictable enough - you've just got to roll your eyes, fix the damn thing and press on, even if you can see the little shits who threw the tacks laughing their asses off.

Put aside any eensy niggles about nuclear obliteration - as Nick Fury so wisely said, "until such time as the world ends, we will act as though it intends to spin on". The planet's future is somewhere on a distribution and, like these poor lushes trying to get to the pub across a bridge over a terrifying ravine of certain-ish doom, there is no point at which it's OK just to say: ah sod it, let's just stumble forward unconsciously and hope for the best. The odds are worsening with every year, but there are - for a good while yet - always odds worth taking. Here's Alex Steffan:

It’s a fight for every 1/10th of a degree. If we fail to hold to 2ºC, we have to fight for 2.1º; failing that, we battle on for 2.2º. With millennia of impacts at stake, we never get to give up, even if we end up in 4ºC. For future generations, 4º is still better than 4.1º. "Game over" is neither realistic nor responsible.

And there isn't a shortage of other stuff to get stuck into. At the root of it all, connecting with others is the prime directive. For anyone who believes every person of any sex/gender/skin-colour/age/wealth/size/shape/geolocation/dress-sense deserves our deepest fucking respect and our care, that we all owe that to each other - that act of connection is the most fundamental and sacred thing we can do. Fucking cliché, I know, but you know that cliché about things being clichés for a reason? That.

To summarise:

1. Fuck them. (Obviously.)

2. Do the thing. Do not - and I really want to be clear on this point - not do the thing.

3. Be excellent to each other.

Now get on with it.

p.s. sorry I was rude about you Donald. I'm really cross with you right now.

Resilience, Yochai Benkler-stylee

Thu, 09/06/2016 - 19:12 — danA superb close to ouisharefest2016 by Yochai Benkler. This in particular:

It's not enough to build a decentralised technology if you do not make it resilient to re-concentration at the institutional, organisational or cultural level. You have to integrate for all of them.

His attack on what happens when all your institutions have homo economicus built into their DNA is sweet and to the point, putting all the words I waste chewing over this stuff in its place.

p.s. 7 out 17 target blog entries? Not gonna complain, that was the biggest sustained burst of non-academic-focused writing for a good while.

Moloch

Tue, 05/04/2016 - 12:26 — danA random thought arising from the Panana papers release - I'll save ranting about the obvious stuff for another time. Looking at a map of 'where the money is hiding' I was reminded of money's mercurial nature. This has been buzzing round my brain for a number of years - not just that it's mercurial, but that it has its own internal logic that gifts it with something that, if you squint, could look like intention.

What the hell do I mean? First-up: my idea of the meaning of 'intention' comes directly from work I did on programming an evolving system of predator/prey 'boids' (this wayback machine link being the only remaining write-up). Both types of boid start out with completely random behaviour. As that article said:

"this means that to start with, some predators, on seeing a preyboid, will try and run away from their food. These poor sods, therefore, don't eat. If predators don't eat, they eventually die of hunger. (Prey only die if they're eaten.) Equally, prey can go for the Darwin award if their random rules send them happily into the jaws of a predator they see."

As they evolve, however, predators learn to chase and prey learn to fly away. And, for me, that's enough to ascribe intention - of the most elemental, blind form, but I think that label fits because, when broken down into its consituent parts, our own intention is nothing more than this.

Michael Pollan's take on corn (vid also) is another way of looking at it: humans are just 'pawns in corn's clever strategy game to rule the Earth'. It has 'domesticated' humans to its own ends and now rules unassailable across vast swathes of the Earth's landscape. Intention? Not the same as humans', but the same basic dynamic is at play - the corn that survives is the corn that carries its genes on. Growth and continuity is the only determinant of success.

See, nice little segue into money there. The idea that humans might be serving money and not vice versa is hardly new. I'm just wondering if thinking about it this way - and considering how something as apparently static as money that couldn't exist at all beyond human support (yet...) could be considered to be pursuing its own goals.

It's an idea that teeters alarmingly close to complete gibberish and madness, all getting a bit Ginsberg. "Moloch whose mind is pure machinery! Moloch whose blood is running money!" (This is a fun piece looking at Moloch as an agent, among other things.) But I think it's still possible to flip the human/money intention view without being too stoned and see something interesting. It's visible in, say, the way that taxis move around a city and stop for people: money looking for ways to move, the driver co-evolved to pilot the machine that does it. As one gets closer to money's most obvious homelands, in the banking sectors, so the human-money symbiosis creates all sorts of bloated weirdness.

And maybe humans aren't really needed for that much these days. Most money movement has nothing to do with us any more, it's all machine-managed, feeding off nanosecond differences in the wires. That we still leave this system actually connected to the human economy may come to be seen as complete insanity - about as wise as trying to keep warm by setting a fire in your front room using all your furniture.

This is obviously nonsense on some levels. Money's own intention looks suspiciously human. If money only wanted to grow, why would it slink off into the rivulets of global tax havens? Tax is still money flowing, after all, and states are plenty good at spending. So yes: there's either (a) something here worth thinking about more or (b) I might as well be stoned.

Still, carrying on with the stonedness... that Moloch article has this goddess/human dialogue:

Everyone is hurting each other, the planet is rampant with injustices, whole societies plunder groups of their own people, mothers imprison sons, children perish while brothers war.

What is the matter with that, if it’s what you want to do?

But nobody wants it! Everybody hates it!

Oh. Well, then stop.

This notion that emergence or corn or money might have its own agenda helps explain why 'just stopping' might be beyond us. We're wedded to various different kinds of symbiotic partners who squeeze those parts of us that they know will keep us doing what we do. We are not sovereign.

---

New year's earnestness 7/17. Ten more by the end April? Err. Well, let's see about hitting double figures...

Humans: nought but shipping containers that need to sleep at night

Mon, 14/03/2016 - 12:06 — dan

On the theme of economic reductionism / turning flesh and blood human beings into cold robot calculators: the central theme running through the PhD and the last project was the effect of distance on economic choices: what people buy, where they buy it from, what/where organisations buy, how they change buying/selling and location together as a single choice set. Which is more-or-less a definition of spatial economics.

One of the ideas that turned out to be very useful for thinking about it is value density. As I use the concept, this is just the ratio of an object's value over 'cost to shift it a unit of distance'. So if it's selling for five pounds and you need to ship it ten miles at fifty pence a mile, its full cost is going to £10 and its value density is ten.

In the usual use of value density, the focus is on weight and bulk. Weight hasn't really been a part of recent spatial economics, even if it's obviously continued to be essential for actual logistics planning. Weber's is the classic work that looks at optimal siting giving inputs, weights and distances - but it's past a hundred years old now and 'proper' spatial economists dismiss it as mere geometry. ('That literature plays no role in our discussion' is all it gets from Fujita/Krugman/Venables.)

But shifting the idea of value density to 'how much it costs to ship per unit of distance' alters this: weight/bulk are important only for how they change that cost. Value density as I'm defining it can also change if, for example, fuel costs go up - which is why the idea ended up being superbly useful. It gets more complex if one starts to factor in time issues (the main reason containerisation transformed the planet was due to its impact on time, not distance) - something that, up to now, I've studiously avoided - so in true quant style, since it's difficult, let's just pretend it doesn't matter for now...)

Value density is a concept that, as far as I can tell, only gets used in the logistics literature - a very applied setting where analysts support decisions about actual production networks. I first heard it mentioned by Steve Sorrell and thought, "wossat then?" Because of this, it doesn't seem to have been used as a 'how do spatial economies work' tool.

It's the 'value' part that makes value density interesting. Because the value of something is determined mostly by its economics, only very minimally by its physical weight/bulk/distance-cost, it can be changed by anything that can add or decrease that value. From a non-spatial point of view, that's trivially obvious: something's real cost drops if, for example, wages rise. But when these two are combined, value density means that changing something's real value also changes how far it can economically be moved. That puts it right at the centre of how spatial economies wire themselves.

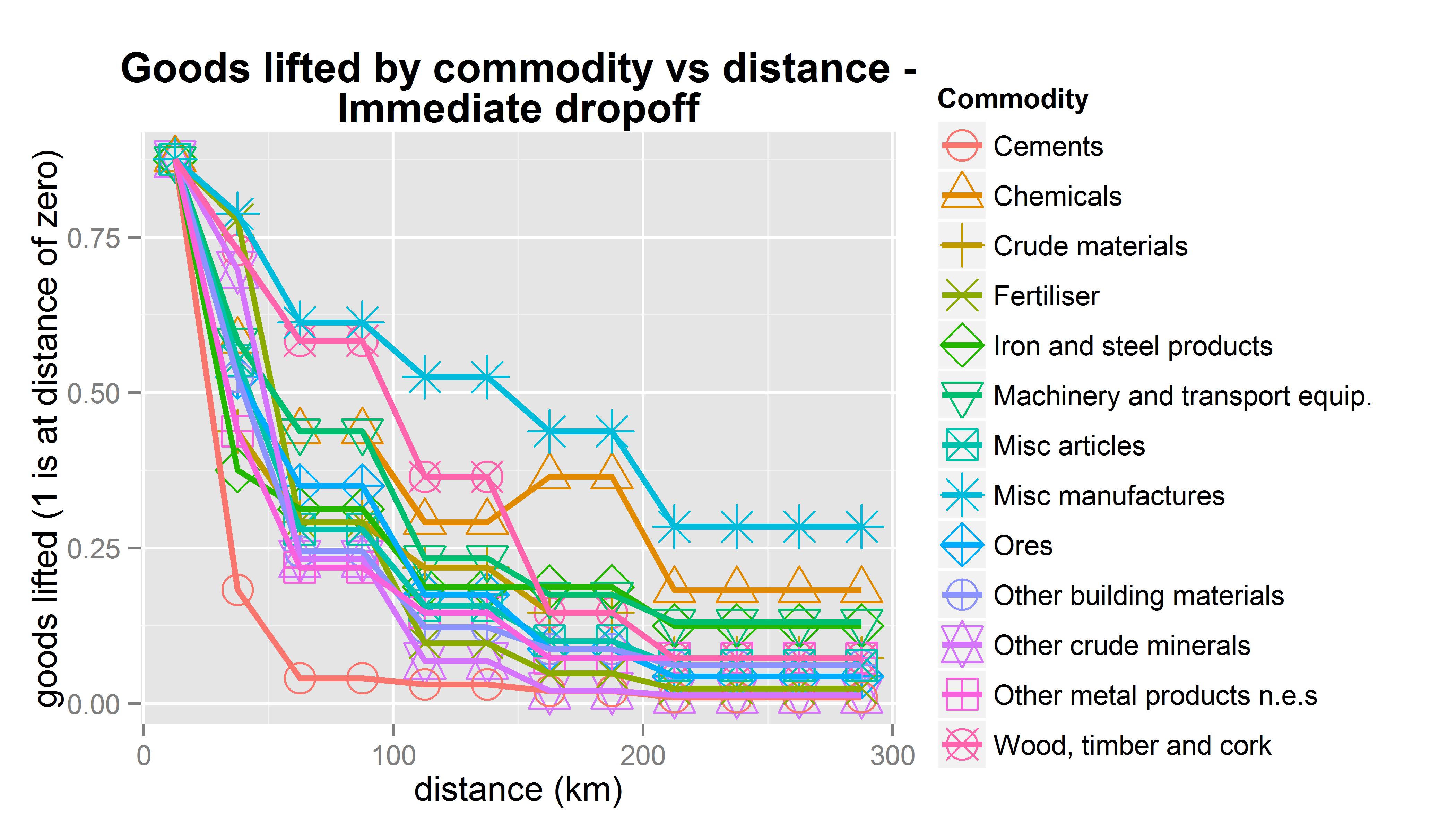

So where Weber cited the weight of certain primary inputs as the reason they don't move very far, logistics folks know that's not it. This can be seen along whole production chains: primary inputs will often need to be close to the first stage of production. At each following stage, more labour is added - and hence more value. Extra value can be added anywhere that extra economies of scale can be squeezed out. This is possibly what determines the dropoff of UK domestic trade (see pics) I dug out of the transport data: low value-density cement, sand, gravel, clay at one end, manufactures at the other (though there are likely plenty of other factors at play, since it's just domestic movement).

This leads to what, for me, seems like a rather startling conclusion: it's the ratio of value to per-unit distance cost, not either alone, that determines the spatial reach of economic networks. This was a very useful idea for the last project as it meant I only needed to determine one number, not two. Again, if we're talking about value versus weight - not a shock, huh? It's when fuel costs or other per-unit distance costs change that it gets interesting. You can increase the spatial reach of your economy by decreasing fuel or time costs - or by increasing value. That can happen through, for example, a more educated workforce with higher wages, through new production methods, through Jacobs-style diversity externalities caused by diversifying clusters - whatever pushes value up.

But there's an exception. There's one input into the production process, one feedstock into the great grinding millstone of the economy, that doesn't quite work in the same way. Human beings. Superb quote:

Humans remain the containers for shipping complex uncodifiable information. The time costs of shipping these containers is on the rise because of congestion on the roads and in the airports while the financial costs of so doing are also rising due to increases in real wages of knowledge workers who are the human containers. (Leamer/Storper, the Economic Geography of the Internet Age, Journal of Intl Business Studies, 2001 p.648).

So humans can be value dense, just like anything else you shift on a truck and back into a factory. But, as production inputs, they have some idiosyncracies that set them apart from coal or crankshafts or hard drives. At the top of the list: with some exceptions (i.e. people who don't stay in one place) they all need to be within a few hours' radius of the place they input their labour. They also have a range of other functions - some of them not even economic! - that determine their spatial patterning. A whole range of essential inputs, for instance, are required to guarantee creation of the next generation of shipping containers for complex uncodifiable information.

Putting aside my flippancy, this is sort of car-crash fascinating to me. It is actually possible to see a quite generalisable theory of value density that just includes some of these tweaks to humans. After all, there's nothing novel about the approach: humans are one side of the most commonly-used production economics idea, the Cobb-Douglas, with capital on one side and labour the other. And we've mostly become blithe to the presence of 'human resource' teams in all large workplaces. But this is a little more specifically economising, isn't it? Not only labour, but an input with certain ratio of value to per-unit distance cost, just with the addition of some tweaks.

I think it works though. That's the marvelous thing. It's this fundamental difference - something explored in detail by Glaeser, for example - that is determining the shape of modern cities. Decreasing distance costs, either relatively through increasing value or otherwise, increases the value density of us lot.

What I'm still not clear on, and why I'm writing all this down: we know that theories change reality. I go on about that all the time. They also change how we see the world individually - obiously, really. Even if there was some clean way of separating out my analysis of how society's structured from my daily world-view, how would that make sense? Don't we try and learn about the world specifically to change how we see it, both as people and collectively?

So I find myself asking the Dr Malcolm question ('Yeah, yeah, but your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn't stop to think if they should'). Not because, of course, it'll actually make me turn off the computer and walk away. At least not yet. But I do wonder - the kind of reductionism I've just laid out might produce genuine insights, but at what cost? I've been wibbling recently about the inseparable link between language networks/production, and this stuff is just another version of that. The cosmology of economics creates some kind of productive landscape - but is it one we want? Should I be comfortable in promoting the use of that language, justifying it with claims that simplifying produces useful views of reality?

---

New year's earnestness 6/17. If Eddie Izzard's having to do two marathons on his last day, I should be able to catch up on the blog target in eight weeks, right? Hmm.

Recent comments

21 weeks 6 days ago

2 years 12 weeks ago

2 years 12 weeks ago

2 years 14 weeks ago

2 years 15 weeks ago

2 years 15 weeks ago

3 years 12 weeks ago

3 years 36 weeks ago

3 years 36 weeks ago

3 years 38 weeks ago