Blogs

The modeller's Hippocratic oath

Wed, 24/02/2016 - 11:42 — danVia this excellent Slate piece on the ethics of big data and machine learning (at the top of my mind after watching a DWP presentation on their forays into the field), there's this article by an ex-finance-worker-now-professor. Three lovely bits. First, their modeller's Hippocratic oath:

This seems especially relevant at the moment as I'm finishing off something I know only tells a partial story, but I also know may be used by some people with an axe to grind. I'm not quite sure what's going to happen yet. Hopefully nothing.

Derman also says:

Unfortunately, no matter what academics, economists, or banks tell you, there is no truly reliable financial science beneath financial engineering. By using variables such as volatility and liquidity that are crude but quantitative proxies for complex human behaviors, financial models attempt to describe the ripples on a vast and ill-understood sea of ephemeral human passions. Such models are roughly reliable only as long as the sea stays calm. When it does not, when crowds panic, anything can happen.

This reminded me of Scott's forest parable: in this case, if the sea doesn't stay calm, perhaps there are ways of calming the sea rather than admitting the model might not be up to scratch. When does the model make the world?

Lastly, Derman quotes Edward Lucas:

If you believe that capitalism is a system in which money matters more than freedom, you are doomed when people who don’t believe in freedom attack using money.

Trump's Nevada win made this seem prescient. A man whose only real distinction is to be very, very wealthy (perhaps despite, rather than because of, his own efforts) ... well, we'll see. This year could end up pretty terrifying.

---

New year's earnestness 5/17. Nearing the end Feb?? Uh oh!

What would happen if new age ideas were left alone to evolve? And other language-related wibble.

Sat, 06/02/2016 - 16:49 — dan

We think of language as a tool for understanding the world - the instruction set used to construct a rational world view. Language and logic have come to be intimately tangled.

But language didn't evolve as a tool for understanding the world - at least, not in the way I've just described - any more than ant pheromone trails did. So there's actually no a priori reason to expect a venn diagram of language and logic to have any overlap. There is a sense in which highly evolved systems can be said to represent an 'understanding' of the environment they're embedded in, but that's not what I mean.

The common thread in the adaptive landscape examples is a mix of adaptation and 'magic' - a web of concepts and speech acts that tie people, place and worldview into a coherent, functioning whole. Lansing in particular does a superb job documenting how an imposed, abstract set of modern ideas about rice-growing were unable to 'see' the Balinese reality because it placed it all the 'superstitious gibberish of no possible value' category.

Those systems make perfect sense if language is seen as a social phenotype like ant pheromones. Yes, there is now a strong bond between language and logic that has gifted us with a collective ability to build a coherent, systematic view of the universe, and one that we can accept as real. There really are billions of stars in the milky way, billions up billions of galaxies in the visible universe. None of that is accessible to us without that bond.

But this social ability of ours should have the power to shock us - as should, say, our ability to read. What on earth prepared the brain for that astounding leap? Converting marks on paper, in neat rows, into comprehensible language? HOW? What else could we do collectively with our language tools?

What I'm trying to get at: there was nothing inevitable about these language features we now take for granted that got built on top of our evolved abilities. And the ones we now have perhaps blind us to the possibility of others emerging. More than that, they may rip them from their mulch just as they're producing the first fresh leaves of growth.

It always amuses me to imagine this happening to New Age ideas - perhaps left alone for long enough, some of them could develop into a genuinely functional social technology, a 'living, breathing, evolving thing: a creature whose sinews were made up of people, story and land'. All the rational snottiness directed at the logical ridiculousness of the ideas involved would be completely missing the point.

Not quite sure I really buy that argument! But that example does highlight why that maybe can't happen. How much scope for organic growth can there be in a world dominated by other, much more powerful social phenotypes that would lay on it like a thick blanket blocking out the sun? On a planet encased in a twenty-four hour clock and so many of us marching so precisely to its pattern? (And anyway, so many New Age ideas are entirely with the grain of that system: commoditised, accessorised, usually appropriated from long-dead cultures in which they may have had actual life.)

There's a cosmic implication too! It's a super-exciting time to be looking at the skies as we're discovering possibly habitable worlds. (That one may be tidally locked - someone's bound to have written some sci-fi about a world with a permanent dark side, right?) And it's fascinating to see how much our search is directed at discovering any other form of life - bacteria, whatever. We don't want to be alone. We want to be part of a much larger story.

To get back to the theme: the Fermi paradox tells us we should, by all rights, be part of a teaming galactic neighbourhood of civilisations. A possible reason I think we're not - perhaps a cross between 'humans are not listening properly' and 'no other intelligent life has arisen' - is due to our misunderstanding this unique, ever-so narrow path language has taken us on.

We see a parochial sliver of the universe, abstracted to the level of our symbolic understanding. This leads us to naturally assume logic and reason must necessarily emerge, as rivers flow to the sea (hence the content of the Arecibo message). But other worlds' views of the cosmos could have taken such radically different paths that, say, the double-slit experiment could be quotidian experience not worth noticing and no form of systematic logic may be part of them.

I'm going a bit 'life Jim but not as we know it' now, but... yeah, that. A famous sci-fi horror story I won't spoil by naming is about a space-faring species who were fiercely technologically advanced but essentially animals. They'd found a particular survival route that built on none of the things we assume must be its predicates.

Plenty of species have independently evolved distributed phenotypes. But as Terrence Deacon says right at the start of the Symbolic Species, when a child asks him why no animals have rudimentary versions of language, humans' particular social phenotype turned out to have some thoroughly unique properties. Life may emerge in many places in the universe - but perhaps this particular ability is phenomenally rare. And even then, there appears to be no reason to expect a smooth slope from language-as-adaptive-landscape to a social lens for seeing the entire cosmos.

---

New year's earnestness 4/17. We'll see if I can catch up on the missed week!

Killing the idea that communal action can solve social problems

Tue, 26/01/2016 - 14:36 — danA famous Orwell quote that crossed my facebook feed:

Whether the British ruling class are wicked or merely stupid is one of the most difficult questions of our time, and at certain moments a very important question.

This 'wicked or stupid' question has been on my mind a lot recently, so it was striking to see exactly the same thought from eighty or so years back. It's the Tories I'm referring to, of course. Caveat: there are many, many decent tory voters out there - good people all. And many decent Tories in politics even. But the bunch actually doing the ruling? Well.

There are plenty of examples to choose from to characterise our current rulers, but let's start with the recent secretive push to scrap what remains of grants for the poorest university students.

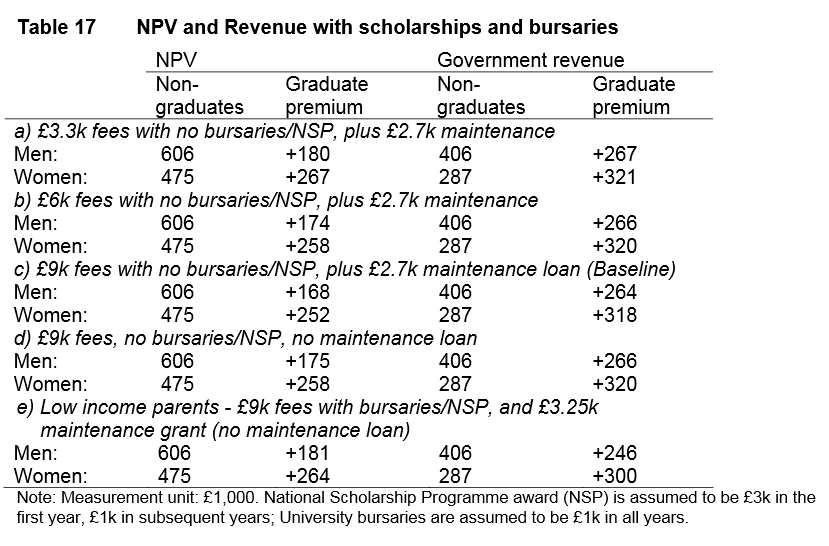

If you google 'lifetime earnings university degree', the first thing that comes up is a report from 2013, funded by the Government's own Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. (Copy here if the official link goes AWOL).

It makes clear the massive benefit of a university education for the person getting it - but also how much benefit is gained by government. I mean, the principle's obvious, right? Someone who earns more over their lifetime will pay more tax. If they end up paying more tax than it cost to educate them, there's a net benefit to the country. The word often used for this, I believe, is 'investment'. I've included the key table - this study has a breakdown by type of student, too, so we can see the gain for individual students who'd be getting the bursaries ('e', at the bottom), as well as the gain to government. The study finds a net government gain of 246 thousand from men and 300 thousand from women.

Even if those numbers were a quarter of this or less, there'd be a net gain for government. For every single student lost who decides they can't afford university any more, government coffers lose out too. Osborne claims these grants are unaffordable - that clearly makes zero sense. Ditto his point about "a basic unfairness in asking taxpayers to fund grants for people who are likely to earn a lot more than them". Taxpayers will gain, not lose out.

And that's before all the gains for the individuals themselves - in earnings and life satisfaction - as well as the increase in education levels for the country as a whole, where there's basic economics telling us the spillover gains over time for everyone.

But this is missing the point, I think - and this is why I think they're cruel, not stupid. It appears stupid only if one assumes they have the same frame of reference. They don't, not at all. No amount of logical argument on the costs and benefits will affect this government's aims. Yes, they use this language of unfairness to taxpayers, but this is little more than effective PR (which is Cameron's background, let's not forget). Flak to cover them in pursuit of the main prize.

The sell-off of housing association properties paid for by selling-off council houses shows the same aim. Housing associations are some of the last living examples of solving social problems communally. The fact that they're actually privately owned makes no difference to that.

So it's not simply a matter of shrinking the state. They actually want to kill the idea that communal action can solve social problems. A smaller state is a consequence of that belief, not a cause - which is why framing student support as an investment would make absolutely no moral or logical sense to this government. They don't see there's anything to invest in.

The NHS will go last, unless something changes. It's their biggest political goal and one that will require all of their PR know-how. They can't quite let the wolves out of the door yet - they know the political ground isn't prepared. But they're very good at this game and blithely content to use whatever bullshit argument will get them to their atomised oligarch utopia.

Hmm. That's interesting. Turns out I'm a bit cross about this.

------

New year's earnestness 3/17 , just.

Migration entropy

Fri, 15/01/2016 - 22:09 — danFor NYE 2/17, I'd like to point you over to the other blog for a combination of a ramble about migration (a part of my new job) and an attempt at some silly R modelling to look at some of the basic stochastics. With some Akala thrown in for good measure. All utterly fascinating, I'm sure you'll agree.

------

New year's earnestness 2/17

How to avoid comparing rich and poor

Fri, 08/01/2016 - 18:51 — dan

Reading Mark Blaug on Pareto efficiency was a lightbulb moment. As he says, Pareto's idea was a 'watershed moment' in arguments about utility. From a distance, the outcome can seem pretty meaningless but it's an important political fork in the road - and one that shines a light on how the abstractions of economic theory get tangled with power politics. There's a story about Pareto himself to be told, too - I'm not going into that. This is about where his idea went after that.

Benthamite utilitarianism hadn't been going badly. But it was premised on the idea that different people's well-being could be compared - after all, there's no other way of knowing if you're increasing or decreasing the general welfare.

This seemed intuitively straightforward at the time. But, perhaps as the study of utility as an economic concept developed, that began to change. Attempts to actually track down a scientific measurement of people's utility got underway. Folks got upset about the obvious problems in trying to define what utility really was.

Pareto offered a way out of this. I'd known the concept before but not understood its significance until reading Blaug. Pareto efficiency: you've reached an optimal state when it's not possible to make anyone better off without making someone else worse off. Sounds innocuous enough. But notice that it sidesteps comparability. As Blaug says:

"The beauty of Pareto’s definition of a welfare maximum was precisely that it defined the optimum as one which meets with unanimous approval because it does not involve conflicting welfare changes."

It rules out the possibility that one could -

" - evaluate changes in welfare that do make some people better off but also make other people worse off" (Blaug / economic theory in retrospect/ 1997 p.573-4).

So it can say absolutely nothing about inequality. Or rather, it implicitly says that it doesn't matter: you cannot, for example, assess whether taking money from one person and giving it to someone else will improve welfare overall. Bentham schmentham.

Pareto optimality, unsurprisingly, became very popular and is essential to most general equilibrium models. I don't understand those - I'm only familiar with Krugman's spatial GE stuff, which is not the same (they're driven by explicit utility differences across space). But I'm not surprised models that, by default, exclude inter-personal comparisons should form the inner sanctum of modern economics. A model that can, by design, exclude any discussion of redistribution was always going to thrive.

Which is not to say there aren't plenty of approaches that do analyse the differences between rich and poor. But... and I'm not on solid ground with this point at all... the kind of economics that sits in rooms with ruling elites don't generally use those.

I want to make two little points about this. The first comes from having actually used utility as a concept in my modelling work and found it extremely valuable. I spent far too long listening to the siren-calls of agent modellers telling me to go towards 'realism', then in the process of slowly solving my problems, realising I had ended up back at basic micro-economics.

So first: if you're going to use utility at all, you'd better accept it's a silly idea that lets you do useful things. People are not actually utility maximisers, but the concept is a superbly effective way of thinking about how people react to cost changes in certain situations. (This is all very Friedman [pdf].)

So all that pursuit of the actual foundations of utility in our meat-brains is, somewhat, beside the point. Given that, we should use the idea in ways that are useful. Ruling out utility comparisons is just a little bit too convenient a result, politically. There isn't really any reason to, and the angst about utility's epistemological status makes about as much sense as rejecting traffic models because they don't use gravity equations. (Er, at least I think they don't...)

Second, one of the most powerful ideas that utility gives us is diminishing returns. It's easy to forget how much of a puzzle this was - the whole water/diamond problem thing. It should be blatantly obvious to anyone who thinks for a few seconds that money itself has diminishing returns. Say a 7% drop in income forces your family to eat less well and you to have to skip meals sometimes. It shouldn't be beyond our economic theory to see this as more severe than having to compromise on the Land Rover you had your eye on by buying a Mondeo.

This is kind of paragraph that sets the flying monkeys off, though. Particularly since the 2008 crash, particularly in the UK - the story that's been slowly pushed through all media channels is solidifying into political reality: such talk is the politics of envy, rather than - as it actually is - a perfectly sensible way to think about wealth.

These days I generally end up thinking "it's all about the middle way". The same applies here - effective economic comparability could imply deep intrusion in people's lives, the state charged with measuring and judging what forms of spending were more worthy than others, creating a kind of state-sanctioned Maslow hierarchy. But it doesn't need to - if one is capable of accepting the basic premise that severe poverty makes people's valuation of money much higher than for richer folk, it just implies the need for policies that reduce inequality.

And there isn't necessarily anything wrong with Pareto efficiency. The problem here is what happens when powerful abstract ideas interact with powerful political forces. Things get warped to Wizard of Oz proportions. Other perfectly sensible ideas can't get their shoe in the door. But it's foolish to use Pareto efficiency to exclude distribution thinking, just as it would be idiotic to ban its use because it was too right-wing.

I wouldn't want to live in a world where political schools had their own paid-for economic theorists. I do still believe in the pursuit of actual social-scientific truths. But Pareto efficiency is one of those ideas that hammers home just how hard it is to pull economics and politics apart.

The point: as far as possible, your economic/mathematical models shouldn't rule out one particular political way of thinking. The choice of how we balance wealth in society - that's a political issue. There's no easy way to keep an unbreachable line between positive and normative - modelling methods will always interact with our political assumptions and power structures in sometimes very-hard-to-see ways. And I also believe in the power of quant modelling to help us understand which things may not work if pursuing certain political aims. But modelling distribution issues - and using utility to do this - no more makes you a communist than using Pareto efficiency makes you a fascist.

(p.s. googling Pareto inequality reminds me there's a mountain of stuff on this subject I don't know. But if I think like that all the time, I won't get a single blog entry written, let alone seventeen...!)

------

New year's earnestness 1/17

New year's earnestness

Wed, 06/01/2016 - 14:46 — dan

Because everyone calls them resolutions and I enjoy being pointlessly antipodal. Anyway, here's one of mine: write a blog entry a week for at least the next four months. Doesn't matter where, though I'd like them to mostly be here on good ol' CiB.

All previous efforts to set myself writing aims - beyond those things that external reality forces me to complete - have not been glorious. But I'm not going to let that stop me from publicly declaring a goal knowing there's a risk of public failure. I like to think I've grown immune to the shame of public failure, so there's nothing to lose in trying again...

The plan: I'll click the publish button every Friday. On the off-chance I've managed to bank some writing, I'll hold off until then. I'm currently in possession of many scraps and ideas so there's plenty to get going with - for a start, there's 38 evernote items tagged 'blog', some of which aren't all that far off publishable.

Navel-gazing moment: writing has become an odd thing of late. I used to love it, and I used to be relaxed. It's the 'relaxed' part I want to get back - having to click 'publish' every week may perhaps help me let go the incredible tension my writing sphincter's been under these past few years.

There's so much happening out there in reality one can bounce words off. Part of the problem has been how I've changed in the face of that. Symptoms of a really, really boringly classic mid-life crisis, possibly: realising that the world is likely to carry on churning its way along much as it always has. The mental construct I used to have about some future point of radical change: a carrot tied to a stick tied to my neck. It's not so much that I don't know what I think any more - it's that I used to imagine I'd know by now, or I'd have lessened the ignorance, or the world might have taken some steps towards me. But I might as well have been bailing the Atlantic into the Pacific. And the world? Who knows - perhaps they're doing OK out there on those planets we've been finding thousands of light years away.

I don't want the up-coming writing to be (just) navel-gazing though. So do come back! It'll be OK! I'd rather kick up some dust from all this ground that's settled in the quiet and see what happens. Poke reality with a stick, step back, observe, poke again... There'll even be some groovy stuff to write about the new job, I suspect. It's turning out to be rather awesome.

Well. I could have just not posted this and kept the earnestness to myself. But then, I wouldn't be able to write a self-congratulatory entry on the first Friday in May. As it is, I might not anyway, but... I might.

This mopey entry doesn't count as my one-a-week. First one this Friday!

Update: there are seventeen Fridays up to / including 29th April. So I can look back and count 'em, I'll mark each entry with its index. So tomorrow's is 1/17. Come May, there'll be no hiding from the gaps!

Patent dystopias

Mon, 03/08/2015 - 09:11 — danGene-sniffing USB devices become tightly coupled to dating (note that one doesn't need a website, you can take it wherever you go and it'll sniff people for you!); facebook gains as much of a monopoly on that as it currently holds in the online `friends' app world; using its vast data, it develops "social and epidemiological compatibility" algorithms; these algorithms form a feedback loop with advertising targeting and revenue; over a period of a few thousand years, Facebook's

Adaptive landscapes 2

Fri, 17/07/2015 - 12:14 — danBack in 2009, I was talking about adaptive landscapes: three real places and the quite different systems that human communities had evolved there to manage them. That was just before the PhD let go of those strands to focus on spatial economics (I'd been, hubristically, trying to combine all those up to that point). Two of those communities are concrete examples of non-centralised social technologies[1] achieving specific resource goals. The Balinese rice system constrains water use in a way that optimises the balance between pest management and productivity. Andean potato production was a magical innovation machine and living, breathing laboratory spread over the hills.

This stuff is still very dear to my heart, and flowed directly from the questions in the original PhD proposal. I want to get on to the adaptive landscapes stuff, but let's lead into that by answering a more straightforward bit from PhD #1.0. Top of the list: was Hayek right about the sacredness of the price system? Was its 'spontaneous order' a singularity in human history, requiring any attempt at planned interference in human affairs to be suppressed? Given what I've just said about Bali and Peru – guess what? Shock: no, I don't think he was. He correctly identified the price system as a distributed social technology, emerging from the uniquely human mix of evolution and language. But, far from being astronomically unlikely, there's evidence that humans are primed to create this sort of structure. I've long entertained a notion that adaptive landscapes are intimately related to the emergence of language itself, Wittgenstein's notion of meaning as a kind of flock tying nicely to that.

Whether that's true, or whether adaptive landscapes were a later innovation built on the platform language provided, makes little difference to their riposte to Hayek: we are natural-born de-centralisers, and we can make systems as diverse as you can imagine. Deifying the price system? Educating the socialism out of people (Hayek acknowledged people have altruistic instincts early in life) so's they didn't get the urge to meddle? Silly.

That's a gross over-simplification of Hayek's thinking and, in particular, I do partly buy his aversion to "planning blindness" and his view that social change should be more like gardening than engineering or construction. (Planning blindness nearly broke Bali's rice management system, for instance.) But it's clear that, if we followed his manifesto to the letter, new adaptive landscapes would have immense difficulty taking root, let alone blossoming.

How wiggly is Britain?

Fri, 03/07/2015 - 20:51 — danI've just had my first go at using R to create a blog post - a pretty pleasing process, actually. I take some previously harvested distance data and... oh, go read about it over there.

Would you trust Uber and Google with your city streets?

Mon, 15/06/2015 - 20:09 — danUber-branded taxis are now ubiquitous* in Leeds, having launched last November. I'm back in Leeds for a month - it was immediately striking that pretty much every taxi now has the large white Uber label, at least in the city centre. That's a pretty impressive transformation in just over six months.

It's a classic disruptive firm; one can imagine CEO Travis Kalanick has personal targets for how many local government authorities to annoy. It can certainly be spun as a nimble tech firm zipping around the tree-trunk legs of a geriatric industry. Predictably, there's been trouble. As well as various protests, some Uber drivers are getting organised to fight for a bigger slice of the profits. (If, as that article says, Uber are taking 20-25% per ride, there isn't a lot of head-room for wages to increase - Uber's dirt cheap fares would have to rise.)

Uber have placed themselves between drivers and customers in a way that reminds me of the weirdness of Apple's app store. In a world where anyone can dump code on their blog and anyone can downoad it, Apple have thrived by creating a portal and sitting as gatekeeper. They take around 30% of every single app sale - and, for developers, this has actually worked out great. They get access to a huge market while getting to code on a single, predictable platform. Small niggles about the political implications of that control might buzz about irritatingly but cause no serious discomfort.

Equally, existing tech could - in theory - link customers and taxi drivers without the need for such a powerful intermediary. The possibility of open-standards platforms transitioning us to the next level of transport has excited many people. Harvey Miller's work, for instance (and this great presentation) sees hope for a "transportation polyculture" where smart-city tech opens up a world of collaborative/co-operative transport. In this world, the kind of fluid, efficient city roads that Uber talk about, where ride-sharing is easy and prevalent, come about via open source principles entirely at odds with Uber's - though such a world would perhaps be just as disruptive to existing taxi firms.

Two radically different internet myths are at the heart of this difference. In one founding myth (as the Economist says) the Net is "the spontaneous result of co-operation by growing numbers of people acting outside the control of the governments and big companies" - a "libertarian paradise" promising a level of openness, connectedness and democracy never before possible. That story is still being told.

But then this other story appears.

Recent comments

21 weeks 6 days ago

2 years 12 weeks ago

2 years 12 weeks ago

2 years 14 weeks ago

2 years 15 weeks ago

2 years 15 weeks ago

3 years 12 weeks ago

3 years 36 weeks ago

3 years 36 weeks ago

3 years 38 weeks ago