At last, the people: Stafford Beer's model of the Chilean economy

I had a couple of bottles of wine and a tangled bank of discussion last night with Andy Goldring. One of those ones where notes must be taken - at least on my part, since I got so many ideas from him. The one I want to write about here is Stafford Beer, a plummy, crazy-bearded cybernetician. After his World War Two service he got into cybernetic management theory, consulting for a load of large companies. I'd heard about his attempt to create a cybernetic economy at some point but never followed it up. It's a fascinating chunk of history. The economic system he designed was called Project Cybersyn; there's a website with films from a documentary / art installation about it, which has a wonderful bit of footage from Beer's time at UMIST. It's accessible via one tiny little pink dot - or if you're impatient, the direct link is in the source of the page - I've kindly put it here for you. [update: video is now on youtube here] The silent UMIST audiovisual timer at the start gives it a convincing sense of antiquity. I recommend watching the first five minutes at least.

One day while working in London in 1971, Beer - to quote from the film -

... got a letter that very much changed my life. It was from the technical general manager of the state planning board of Chile. He remarked in this letter that he had studied all my works, he had collected a team of scientists together, and would I please come and take it over? I could hardly believe it, as you can imagine. But this was to start me on a journey that had me commuting 8000 miles over and over between London and Santiago.

Stafford Beer's viable systems model is organic; the functions he maps out look like a human body. (Not the first time anyone had made an organicist comparison with the body / nervous system / organs / brains; could Hobbes take that accolade?) As one might expect, it's an obsessively detailed and totalising set of ideas. There are five 'systems'. System 1 is the organisation itself - a body / company / state; system 5 is the equivalent of a brain. The others have various feedback and environmental adaptation roles.

So - Beer outlines this system to Allende, who was a trained medical doctor, so the comparisons were clear enough to him. Here's Beer again -

And so I said to him, let us suppose that these elements of the state are the big departments of state: foreign affairs, the economy, home affairs and so on. And the following things will happen, and we must have a 'system 2'... and I built it up on a piece of paper lying on the table between us. Then a system 3 and a system 4, and I got that far. And then I got to system 5 - and I drew a big, histrionic breath, and I was going to say, 'this Companero Presidente, is you!'

Before I could say it, he suddenly smiled very broadly, and he said, 'Ah! System 5. At last - the people.' That was a pretty powerful thing to happen. It had a very big influence on me.

In Beer's work in Chile, this moment seems to have led to his theory of 'algedonic meters'. Algedonics, according to Beer, 'means pleasure and pain.' (It literally does!) This principle underlay all feedback systems in Beer's model of Chile, building in that 'we had to get a response from the people to everything we were doing. And we made some profound plans to achieve that, and again not part of this story, and not completed.'

Beer then asks:

how do you control an economy? As we sit in England, we may feel, well - the answer to that is, you don't.

He quotes Macmillan: 'running the economy is like trying to catch a train using last year's timetable.' Economic data in Macmillan's time was 'about a year out of date'. He notes that Wilson reckoned they'd improved that to six or eight months. It's an interesting comparison to how the economy is steered now; pretty much the only macro-economic tool available is interest rates, and that's no longer a government decision. Also, as many an economist has noted, changes in rates can take up to two years to have any impact. Beer makes the same case, but from the other side, as it were: the data such a decision is based on is always out of date to start with. It's like trying to steer a car with a time-delay steering wheel through a camcorder viewer that relays what was happening ten seconds ago.

Beer's answer was immediate information. In discussing the problems of how and what to measure, their goal seems to have been to get an awful lot of data - everthing from production levels to absenteeism. But Allende's Chile was poor; it was blockaded, for a start. So they had to build their cybernetic system out of telex machines, stretching the full length of Chile's narrow strip down the Western edge of South America. He presents his telex / computer model - and then has a dig at those who blamed him for centralising power in the Chilean economy and building autocratic structures.

These data were not used in an autocratic way at all. It all went to one computer because we only had one computer. If you've only got one computer you're ipso facto centralised - but we were not centralised in the political sense that this has been taken up by some critics.

In the film, Beer takes some time at a blackboard to demonstrate what the computer system would do with any single datapoint - all of which, it appears, have values between 0 and 1. He's obviously very proud of this - an automated system called Cyberstride calculates whether any extreme points are transients, step-changes or trends.

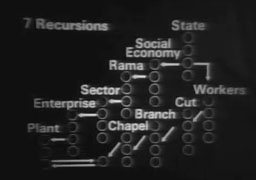

Recursion is very important to Beer - his model is all about nested systems (see the pic of nested firm / sector / branch - and, above that, whole economy.) They actually applied this to the 60% of the economy that was nationalised at the time. People in various decision-making positions were asked how long they would need to make a decision when data came to them. This was built into the model: feedback stayed within one level - e.g. a specific factory - unless a response to data was not forthcoming within that time - then the data would travel up the system another level. The 'algedonic signal' indicates 'pain' at various points in the system this way; pleasure, it seems, is presumed by an absence of data. Beer is adamant that, if any one level responds successfully to data (whatever that means) the signal goes no further, and autonomy is kept. (Er... I'll save my criticisms and stick to description for now...!)

He does make an interesting point about variety - what we'd probably call complexity now - which also gives a tiny glimpse into the megalomaniac core beating in his heart:

What we have done is to choose at which points to cut down variety so that it can get into the brain. Only people can do anything about anything, and they can't do it if their brains don't get the message. They need a huge variety attentuation. Now, in most of our society, this is done by accident. It's done by averages that swamp those little bits of information that give you most advanced warning. It's done by pressure - lobbying people and urging a point of view, rather than by data at all. All those things, I don't have to go through them.

He personally doesn't have to go through them? Mm. Next is a wonderful passage:

What I tried to do in Chile was to use the model to design freedom. Because this system was meant to put stuff where it was wanted. (Nationalised industry, remember.) These people need these materials - get them to them in time. These people need that - get it to them. These people can deliver to the public - help that to happen. All these points chosen, and this whole system given a management structure, which could monitor such a thing with adequate variety - using, I repeat, clever computer programs, and not just talking about electronic data processing - y'know, you want some information, we have some: a print out this thick.

The Wikipedia entry about Beer includes a photo of the Cybersyn control room - a perfectly kitch star-trek rendering of exactly the sort of thing that would make Hayek pull a face like this (p.s. if you're going to do an image search for Hayek, do something like 'friedrich hayek -salma': otherwise the result can be quite a jolt if you're expecting an Austrian economist...)

The control room picture captures in one image exactly the sort of fears Hayek articulated: a small cabal of Bond-villains in retrofuturist chairs oppress the people without even having to lift an arm. So it's interesting that Beer placed so much emphasis on 'the people' and building in controls that at least aimed to devolve power and provide mechanisms for dissent, even if the practice may not have turned out that way. (The US made sure we were never to find out. As Kissinger said, 'I don't see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people. The issues are much too important for the Chilean voters to be left to decide for themselves.')

Beer talks at length about the fact that the kind of economic data we use now is only legible to specialists - and would have been of little use to the Chilean worker's who ran the syndicates. (Much the same point that James Scott makes about the zero-sum of state-maps, though see this recent Crooked Timber post suggesting state map-making might not be so zero-sum.)

(He also spends a good chunk on the reasoning behind the control room around the 38th minute of the UMIST film. It has some beautiful moments: 'each of these three screens underneath is driven by no less than five carousel projectors, each with eighty slides, so you see we've got a huge information capacity.' Crikey. At any rate, his central aim is to provide data that's in a legible form to human brains. His obsessive attention to detail is evident: seven chairs because 'any more and things get too formal - psychology shows that seven people is about the right number of brains to really bash something about.' He also notes that any man - and he does seem to have designed it solely for men - using a chair can 'strike his nob', which gave me a cheap laugh; also each chair has an ashtray and a drinks holder - more than James T Kirk ever had, the poor sausage.)

The striking thing is, of course, that despite the caricature the 'control room' represents, Beer's description of a 'design for freedom' is exactly what economic thinkers from Hayek to David Friedman (author of the Machinery of Freedom) claim for economics. Who feeds Paris? The economy! A perfect, globally distributed freedom-computation device, using price signals to figure out what everyone needs with no human hand required. Indeed, attempts at intervention would be pouring sand into a well-oiled machine. The nub of the difference between the two systems? As the Idea Shop says, regarding the economic calculation debate -

By pointing to recent advances in computer technology, advocates of market socialism claim to have refuted Hayek's entire position by showing that data transmission and 'equation solving' would not pose serious problems under socialism. Hayek's central argument, however, was not so much that a socialist economy could not transmit the necessary data, but rather that it could not generate it to begin with. Without the competitive process of discovery and innovation, a socialist economy would have available only a small fraction of the knowledge that is utilized in a competitive economy. The task faced by proponents of market socialism is to explain exactly how spontaneous discovery is to occur within a planned economic system.

Also, Hayek wasn't against planning: he had no problem with corporations doing it internally, or the fact that workers may have little or no autonomy there. As long as there were many centres of power, none able to get an upper hand, he was a happy chicken. The machinery of freedom was the constitution of liberalism, as it had evolved to be embodied in the institutions of the 'Great Society'.

But then, that's odd. Beer argues that the machinery of freedom is built into his system, just as Hayek argues it's woven into our evolved institutions. So why can it be built into the machinery of institutions, but not the machinery of machinery? Both would need checks and balances, but there's no reason why that's not possible.

In a little serendipitous moment, Google delivered me a word alert for 'tescopoly' today that led to a couple of brilliant blogs: Blood and Treasure talks about a 'Gosplan that works' - Tesco, noting:

One of the things that amazes me about Tesco is the sheer amount of agonizing and general sturm und drang about an entity that is really no more than a massive, open ended logistics chain. In many respects, it's a classic Fordist business, heavily dependent on standardization and with market share the main factor in profitability. It demonstrates that massive, centralized, top down hierarchies can work, provide they pay enough attention to actually expressed public preferences. It's the profit motive harnessed to the perfection of the Soviet Union. It's Gosplan that works.

(Here's the blog that got me to this with a sentiment that fits with my current wavering on whether Tesco is evil or Knievel.)

It's better than Gosplan because now, as this review of two insanely expensive volumes about on 'nature-inspired computing for economics and management' shows, corporations are lapping up systems that would make Beer wet himself. The example I'm always fond of - Dell's ability to balance out supply chain bottlenecks by altering the price of alternatives automatically to telesales staff. ("For today only, sir, we're offering the 80gig hard drive for the same price as the 40. Would you like to upgrade?") That's a slightly whimsical example when compared to any major corporations' achievements. Tesco or Toyota both use reflexive systems designed to feed market signals into labrynthine supply chains consisting of thousands of different firms, and they both manage to get things in shops exactly when someone wants them. (Whilst also managing to somehow have difficulty checking which of those suppliers holds on to their trafficked worker's passports to stop them leaving the UK. Odd that.)

Andy might say: well, yes, that's the whole point. The US was happy for Beer to consult companies with a '30% efficiency savings or your money back' promise. The problem arose when that system threatened to demonstrate an alternative to capitalism. I don't know if I agree with this, but it's just plausible enough to be not quite a nutty conspiracy theory - particularly as the reflexive, computationally advanced children of cybernetics continue to improve corporate profits daily.

If Beer's story about Allende is true - and it has the sound of something mythical enough to be a total fabrication - it means they believed it was possible to build people's needs into an economic system. That is, everyone's needs, not just 'the consumer'. The great thing about economies, ostensibly, is that this isn't needed. The fact that people act selfishly is no bar to the emergent result being the best of all possible worlds. In fact, as Hayek argued, it's vital to 'educate' any remnant fellow feelings of solidarity out of us early, because they're a dangerous evolutionary maladaptation, no longer relevant in the newly evolved Great Society that's superseded it. As Thatcher said (presumably after one of her private lessons from Hayek):

Economics are the method - the object is to change the soul.

Recent comments

21 weeks 6 days ago

2 years 12 weeks ago

2 years 12 weeks ago

2 years 14 weeks ago

2 years 15 weeks ago

2 years 15 weeks ago

3 years 12 weeks ago

3 years 36 weeks ago

3 years 36 weeks ago

3 years 38 weeks ago